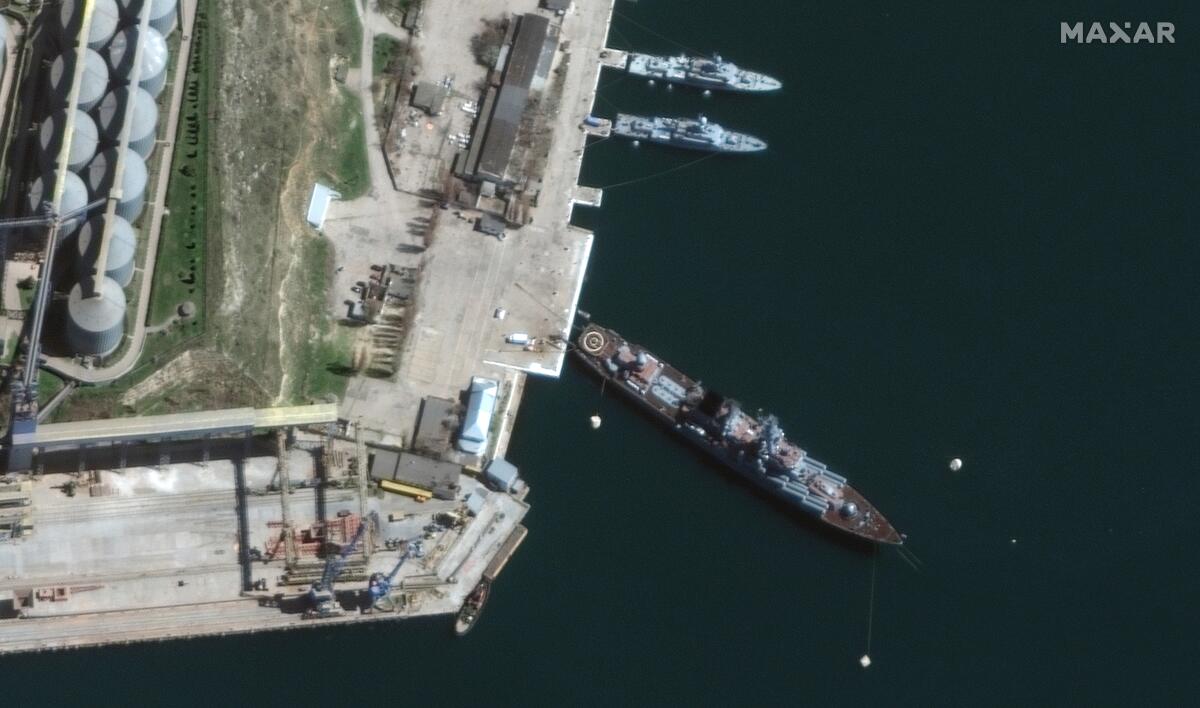

After Ukrainian missile attack, Russia reports its Black Sea flagship sank while being towed

Russia’s most important naval ship in the Black Sea sunk Thursday after apparently being struck by a Ukrainian missile, a turn that came as Russia continued preparations for a major offensive in eastern Ukraine and one of its senior officials threatened Finland and Sweden for expressing interest in joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Ukrainian officials in the port city of Odesa reported overnight that a Neptune missile had been launched at the Russian ship, the Moskva, which has been part of the naval campaign against Ukraine. There were conflicting reports as to whether one or two missiles were fired at the ship.

Pentagon press secretary John Kirby said he could not confirm that a Ukrainian missile struck the ship, only that there had been an explosion on board that caused a “raging” fire.

The Russian Defense Ministry, which had acknowledged the fire but did not provide a cause, later reported that the ship sank while being towed in a storm, according to state-run media.

The sinking of the Moskva is a major blow for the Russian fleet and a tactical and public relations coup for Ukraine at a pivotal moment — when the country is bracing for a massive Russian offensive.

Ukrainian officials said the Moskva, which reportedly carried an array of missiles, torpedoes, mines and other weaponry, had a crew of 510. It was previously deployed in the Mediterranean off the coast of Syria, where Russia has aided the government of Bashar Assad against Western-backed rebels.

Although the U.S. says it’s committed for the long haul, there’s no evidence it has a plan to shorten or help Ukraine in what’s shaping up to become a protracted conflict.

The Moskva was also involved in one of the signature confrontations in the early stages of the war. The ship’s crew demanded the surrender of a military unit posted on Ukraine’s Snake Island in the Black Sea. The Ukrainians are said to have answered the Russians with a defiant refusal punctuated with profanity.

Snake Island’s defenders were taken captive by the Russians but later released in a prisoner exchange. Their adamant refusal to give in has become a kind of motto of Ukrainian resistance, even commemorated in a postage stamp.

Russia has faced a series of strategic and tactical setbacks since its Feb. 24 invasion, including the failure of its forces to seize the capital, Kyiv, and its retreat from other cities in the north.

Western officials have worried that Russian President Vladimir Putin — who earlier in the war hinted at the prospect of resorting to battlefield nuclear weapons — may become more aggressive if his forces come under increasing pressure by Ukrainian fighters armed by the U.S. and its NATO allies.

Clearly concerned about the possibility of an expanded NATO — the pretext for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine — Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chair of Russia’s Security Council, warned that Russia would “more than double” its military forces on its Western flank if Sweden and Finland join the military alliance.

Ground forces would be increased and Russia would deploy “significant naval forces” — with nuclear capability — in the Gulf of Finland, he wrote on the messaging app Telegram.

He was responding to a news conference a day earlier in which Prime Ministers Sanna Marin of Finland and Magdalena Andersson of Sweden expressed a deeper interest in NATO membership, given the invasion of Ukraine.

The big battle for eastern Ukraine is coming, but in the south, Ukrainian soldiers have pushed back the front lines of Russian forces.

“I think people’s mind-sets in Finland, also in Sweden, changed and [were] shaped very dramatically because of Russia’s actions,” Marin said.

Meanwhile, U.S. officials raced to get the bulk of an $800-million aid package to Ukraine in preparation for the looming Russian onslaught.

Kirby said that the Pentagon is “mindful of the clock” as it transfers the latest security assistance to Ukraine and trains Ukrainians to use new equipment.

“We have not seen any Russian efforts to interdict that flow,” he said. “Flights are still going in to tranche shipment sites in the region, and ground movement is still occurring of this materiel inside Ukraine every single day.”

Russia’s broad strategy is to expand its hold on the east and link that with gains it has been making in the south, where it is focused on the strategic port city of Mariupol.

Russia has said the city is under its control, but Ukrainian officials say their forces continue to resist.

Fighting continued to rage there Thursday. Home to more than 400,000 residents in prewar days, the city now has a population of fewer than 100,000 residents.

Authorities say there is little food, water, electricity or heat. But fleeing would involve a perilous run through a gantlet of shelling, gunfire and checkpoints of two rival armies.

The situation was much different in the eastern city of Kramatorsk, six days after 57 civilians were killed and more than 100 were injured after what was suspected to be a Russian Tochka-U missile armed with cluster bomblets struck the train station there.

Train service from Kramatorsk was suspended following the attack, but hundreds crowded into the bus station to evacuate.

As rain beat down Thursday morning, more people trickled into the station, dragging what little luggage they could manage to a pair of buses headed west.

Kramatorsk resident Oleksandr Ivanov, 38, with the Ukrainian aid group “Everything Will Be OK,” estimated that anywhere from 40,000 to 50,000 people remain in the city.

“They fall under three categories,” he explained. “Many don’t have money and can’t pay to stay somewhere else. Second are those whose family members are too old or too sick to move. And perhaps a small part feel that even if Russia comes they’ll be fine.”

Ukraine, with international help, needs to begin data gathering on Russian atrocities before evidence gets lost and victims scatter or disappear.

To the north in Kharkiv, which had a population of 1.4 million before the war triggered an exodus, residents who remain spend much of their time sheltering in an underground metro system. Authorities said the city has faced relentless shelling in recent days.

In eastern Ukraine, Russian forces continued pounding cities and towns Thursday in the prelude to the expected offensive in the country’s former industrial heartland, the region known as the Donbas.

Satellite imagery and Pentagon observation have shown a growing buildup of Russian forces and heavy equipment — including helicopters and artillery — in various staging grounds.

“Russian troops are stepping up activity in the eastern and southern directions,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said Wednesday. “New columns of equipment are being brought in. They are looking for reserves.”

Russian forces in the east are fighting alongside battle-tested Ukrainian allies who know the terrain, an advantage Russia didn’t have during its failed assault on Kyiv that resulted in an ignominious retreat this month. Two pro-Russia breakaway areas of the Donbas have been at war with the Ukrainian government since 2014 in a brutal conflict that has cost thousands of lives.

Western nations have been accelerating shipments of military supplies to Ukraine.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has pushed up already high fertilizer prices and made scarce supplies even harder to find, especially in the developing world.

Putin has accused Washington of wanting to drag out the war in order to devastate his nation. And he asserts that U.S. efforts to bolster democracy in Ukraine and other former Soviet satellite states are meant to undermine Russian security.

“The United States is ready to fight with Russia until the last Ukrainian,” Putin said this week.

Moscow says the invasion, which Putin refers to as a “special military operation,” is designed to help shield Russia from Western encroachment and to demilitarize and “denazify” Ukraine. Ultranationalists, some with Nazi sympathies, have been part of the Ukrainian political panorama in recent years. But they play a minor role in the nation’s political and military leadership.

Since the Russian retreat from Kyiv, a steady flow of foreign leaders has been visiting the capital. That group expanded this week to include the presidents of neighboring Poland as well as the Baltic states — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

They were taken to see firsthand one of the area’s worst-damaged towns, Borodyanka, where Russian shelling and bombardment destroyed a number of high-rise apartment buildings and other structures.

At a news conference in Kyiv after the tour, Polish President Andrzej Duda offered his reaction: “This is not war, this is terrorism.”

McDonnell reported from Kyiv, Bulos from Kramatorsk and Kaur from Washington. Times staff writer Kurtis Lee in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.