Migrants who died in truck in Texas cleared inland checkpoint, U.S. official says

- Share via

SAN ANTONIO — The tractor-trailer at the center of a human-smuggling attempt that left 53 people dead had passed through an inland U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint with migrants inside the sweltering rig earlier in its journey, a U.S. official said Thursday.

The truck went through the checkpoint on Interstate 35 about 25 miles northeast of the border city of Laredo, Texas.

The official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss an ongoing investigation, said there were 73 people in the truck when it was discovered Monday in San Antonio, including the 53 who died. It was unclear if agents stopped the driver for questioning at the inland checkpoint or if the truck went through unimpeded.

The disclosure brings new attention to an old policy question of whether the roughly 110 inland highway checkpoints along the Mexican and Canadian borders are sufficiently effective at spotting people in cars and trucks who enter the United States illegally. They are generally located within 100 miles of the border.

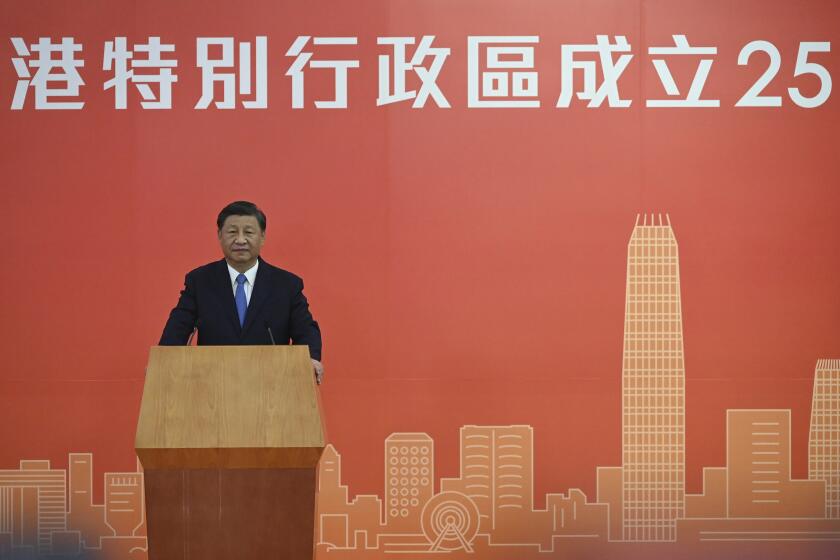

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits a vastly transformed, Beijing-controlled Hong Kong, which is now ‘just another Chinese city,’ one expert says.

Texas state police also announced they would operate their own inland checkpoints for tractor-trailers on the orders of Gov. Greg Abbott, who considers the Biden administration’s efforts insufficient. It was unclear how many trucks they would be stopping.

Also Thursday, Homero Zamorano Jr., 45, the alleged driver of the tractor-trailer, made his initial appearance in San Antonio federal court. During a hearing that lasted about five minutes, Zamorano, wearing a white T-shirt and gray sweatpants, said very little, giving yes and no answers to questions from U.S. Magistrate Judge Elizabeth Chestney about his rights and the charges against him.

The judge appointed a federal public defender for Zamorano as well as a second attorney since the smuggling charge he faces carries a possible death sentence. She scheduled a hearing next week to determine whether he is eligible for bail.

It remained unclear just how long the migrants were in the trailer on the sweltering day and whether having their cellphones confiscated by the smugglers before being placed inside contributed to the high death toll. Emergency calls from trapped migrants have not emerged in this case as they have in earlier incidents.

On Thursday, José Santos Bueso of El Progreso, Honduras, said his daughter, 37-year-old Jazmín Nayarith Bueso Núñez, told him in their last conversation that she was in Laredo, that the smugglers were going to take their phones and she would not be able to communicate for a time. She last messaged her 15-year-old son around midday Monday, saying they were about to head to San Antonio and she would be out of contact.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1976 that Border Patrol agents may stop vehicles at inland checkpoints for brief questioning without a warrant, even if there is no reason to believe that they are carrying people in the country illegally. Still, the practice has galvanized immigration advocates and civil libertarians who consider checkpoints ripe for racial profiling and abuse of authority. Some motorists post videos to social media accusing agents of heavy-handed, inappropriate questioning.

The Laredo-area checkpoint is on one of the busiest highways along the border, particularly for trucks, raising the possibility of choking commerce and creating havoc if every motorist is stopped and questioned.

Border Patrol officials call the checkpoints an imperfect but effective second line of defense after the border, acknowledging that agents must balance law enforcement interests with disrupting legitimate commerce and travel.

Volume and configuration vary widely among checkpoints, but agents generally have five to seven seconds to decide whether to question a driver, said Roy Villareal, former chief of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector.

“Ultimately, it’s very difficult to ascertain with crime in general,” Villareal said. “It’s hard to say whether you’re 100% effective, 50%, 10%.”

U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas), who drives through the checkpoint almost weekly, said investigators believe the migrants boarded the truck in or around Laredo, though that is unconfirmed. That would be consistent with smuggling patterns: Migrants cross the border on foot and hide in a house or in shrubbery on U.S. soil before getting picked up and taken to the nearest major city.

Even if the truck were empty, it would raise questions about the checkpoints. Migrants often perish trying to circumvent checkpoints, getting dropped off before reaching them with plans to get picked up on the other side. In Rio Grande Valley, the busiest corridor for illegal crossings, migrants walk through sweltering ranches to avoid a checkpoint in Falfurrias, Texas, about 70 miles north of the border.

The Government Accountability Office reported this month that agents at inland checkpoints detained about 35,700 people believed to be in the U.S. illegally from the 2016 to 2020 fiscal years, only about 2% of all Border Patrol arrests. Agents seized drugs nearly 18,000 times during that period, with more than 9 of 10 arrests involving U.S. citizens.

The checkpoints have been a trap for U.S. citizens carrying even small bags of marijuana. About 40% of pot seizures at Border Patrol checkpoints from fiscal years 2013 to 2016 involved U.S. citizens with an ounce or less, according to an earlier GAO report.

Abbott did not provide details on the extent of Texas’ new inland inspections announced Thursday. Lt. Chris Olivarez, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Public Safety, said troopers would take a “more aggressive stance.” Asked if that meant stopping every truck, Olivarez said that he did not know and that it would partly depend on staffing.

“It’s going to be inspecting more than what we usually inspect,” Olivarez said.

In April, gridlock resulted at Texas’ border for a week after Abbott issued orders that troopers inspect every tractor-trailer entering from Mexico as part of his ongoing fight with the Biden administration over immigration policy. Those inspections, which were mechanical and safety inspections, did not turn up any migrants or drugs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.