English Channel deaths underscore risks for migrants despite U.K. efforts

- Share via

LONDON — Five more people died in the English Channel on Tuesday, underscoring the risks of crossing one of the world’s busiest sea lanes in overloaded inflatable boats, just hours after British lawmakers approved a controversial bill to stop the traffic.

The migrants, including a 7-year-old girl, died when their boat got stuck on a sandbank off the coast of Pas-de-Calais in northern France. The French navy rescued 49 people, but 58 others refused to disembark and continued on toward Britain, local authorities said in a statement.

The vessel was just one of several small boats packed with people that took off from the French coast early Tuesday, as calm weather enticed them to attempt the crossing. The overcrowded boats are being monitored by drones, French maritime authorities said.

Just a few hours earlier, the U.K. Parliament approved legislation allowing the government to deport to Rwanda those who enter the country illegally. While Prime Minister Rishi Sunak says the plan will deter people from risking their lives on the channel, human rights groups have criticized it as illegal and inhumane.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak quelled a Conservative Party rebellion and got his stalled plan approved, but hurdles remain before any flights take off.

“If you look at what’s happening, criminal gangs are exploiting vulnerable people; they are packing more and more people into these unseaworthy dinghies,” Sunak told reporters on a trip to Poland. “That’s why, for matters of compassion more than anything else, we must actually break this business model and end the unfairness of people coming to our country illegally.”

The number of migrants crossing the channel in small boats has soared in recent years as people fleeing war, the effects of climate change and economic uncertainty seek a better life in Britain. They pay smugglers thousands of dollars for the crossing, hoping to reunite with family members or find work in a country where immigration enforcement is seen as weak and where migrant groups from all over the world can easily melt into society.

Human rights organizations say the way to stop the trafficking is for countries to work together to provide safe and legal routes for migrants, not for countries like Britain to put up barriers and outsource their problem to others.

But even allies Britain and France have struggled to sufficiently coordinate efforts to reduce the number of those crossing the English Channel in small boats. The U.K. has struck a series of deals with France to increase patrols of beaches and share intelligence to disrupt smugglers — all of which have had only a limited impact.

Britain’s effort to send some asylum seekers to Rwanda was swiftly condemned by both the United Nations’ refugee agency and the Council of Europe, which called on the U.K. to rethink its plans.

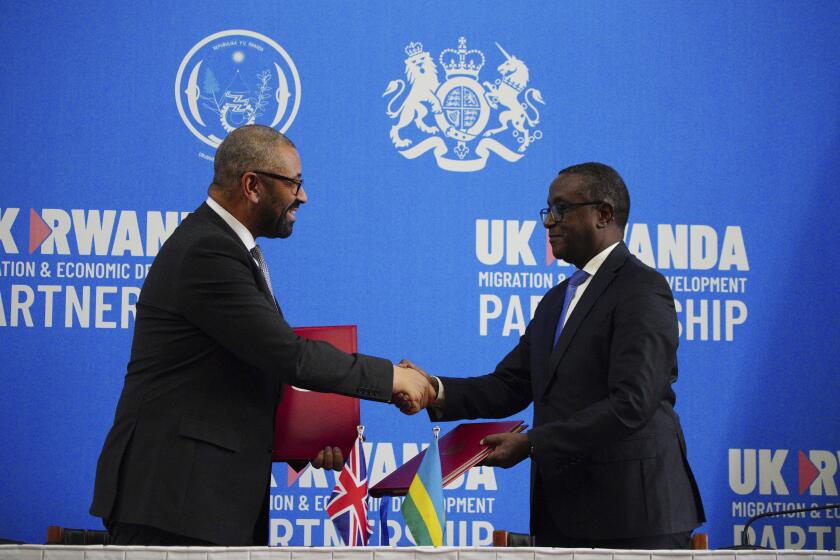

The interior ministers of Britain and Rwanda have signed a treaty that aims to revive a plan to send asylum-seekers to the East African country.

“The new legislation marks a further step away from the U.K.’s long tradition of providing refuge to those in need, in breach of the Refugee Convention,” U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said in a statement. “Protecting refugees requires all countries — not just those neighboring crisis zones — to uphold their obligations.”

Small boat crossings are a potent political issue in Britain, where they are seen as evidence of the government’s failure to control immigration.

Sunak has made his plan to “stop the boats” a key campaign promise with his Conservative Party trailing badly in opinion polls ahead of a general election later this year.

The number of migrants arriving in Britain on small boats soared to 45,774 in 2022 from just 299 four years. The figure dropped to 29,437 last year as the government cracked down on people smugglers and reached an agreement to return Albanians to their home country.

Former Prime Minister Boris Johnson first proposed the Rwanda plan more than two years ago, when he reached an agreement with the East African nation to accept some asylum-seekers in return for millions of dollars in aid. Implementation has been held up by a series of court challenges and opposition from migrant advocates who say it violates international law.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is under pressure to explain why Britain has paid Rwanda $300 million as part of a blocked asylum plan.

The deportees will be eligible to apply for asylum in Rwanda but they won’t be allowed to return to Britain.

The legislation approved early Tuesday, known as the Safety of Rwanda Bill, is a response to a U.K. Supreme Court decision that blocked deportation flights because the government couldn’t guarantee the safety of migrants sent to Rwanda. After signing a new treaty with Rwanda to beef up protections for migrants, the government proposed the new legislation declaring Rwanda to be a safe country.

The Rwandan government welcomed approval of the bill, saying it underscores the work it has done to make Rwanda “safe and secure” since the genocide that ravaged the country 30 years ago.

“We are committed to the migration and economic development partnership with the U.K. and look forward to welcoming those relocated to Rwanda,” government spokesperson Yolande Makolo said.

Kirka and Surk write for the Associated Press. Surk reported from Nice, France. AP writer Ignatius Ssuuna in Kigali, Rwanda, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.