A rift grows in Europe over recognizing Palestinian state

- Share via

For decades, Western Europe has largely spoken with one voice on the subject of Palestinian statehood. Now cracks are appearing in that consensus.

Ireland, Spain and Norway on Wednesday declared their intention to recognize Palestinian statehood, effective Tuesday. Previously, only seven of the 27 European Union member states had made such a pronouncement.

Norway is not a member of the bloc, but the Spanish and Irish announcements will bring the number of EU countries recognizing Palestinian statehood to one-third of its membership.

While the often-fractious bloc is unlikely to act as a whole on the question, EU members Slovenia and Malta have signaled they may extend recognition as well, and concerted lobbying efforts are underway in several other member states, including Belgium.

“There’s a certain momentum there,” said Khaled Elgindy, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Middle East Institute.

Even as major Western powers refrain from recognition, the round of announcements illustrates yet again how the devastating war between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas is complicating traditional Western alliances — both within the EU and in transatlantic ties.

For the last two years, Washington and the EU have been largely focused on presenting a united front on the war in Ukraine, and on the growing closeness of Russia and China. But Gaza has shaken up diplomatic priorities.

Analysts say Wednesday’s announcements primarily point to fundamental disagreements among Western allies over whether recognizing a Palestinian state now — usually a prelude to establishing diplomatic ties — will spur or hinder a future state’s establishment.

The Biden administration supports the creation of a Palestinian state, existing side by-side with Israel, but says recognition should be the result of political negotiations — a view backed by key European partners including Britain, France and Germany.

But the issue is a nuanced one. Britain’s foreign secretary, David Cameron, ruled out recognizing a Palestinian state while Hamas remains in Gaza, but said it could occur in the context of ongoing peace negotiations.

And Germany, shadowed by having perpetrated the Holocaust, supports a two-state solution, but has been unwilling to extend Palestinian statehood recognition in the meantime.

The war’s horrific toll in Gaza, where more than 35,000 Palestinians have been killed, has galvanized some governments to support any moves they believe might set conditions for a cease-fire.

Israel-Hamas war: In Qatar’s capital, a compound housing Palestinian medical evacuees from Gaza is a living catalog of what war does to the human body.

“Recognition is a tangible step toward a viable political track leading to Palestinian self-determination,” said Hugh Lovatt, a senior policy fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations.

But he said without further measures, the recognitions risked being essentially symbolic.

“To be impactful, recognition of Palestine must be matched with tangible steps to counter Israel’s annexation and settlement of Palestinian territory — such as banning settlement products and financial services,” he said.

Religious Zionists, most believing in a divine right to govern, now have outsize influence in Israel. The war in the Gaza Strip is energizing their settlement push.

The differing takes on recognition point to the ways in which European states’ own histories can lead them along distinct foreign-policy paths when it comes to the Mideast.

“Each country’s story is different — it’s very idiosyncratic,” said Elgindy, who directs the Middle East Institute’s program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli affairs.

Ireland’s prime minister, for example, specifically cited his country’s lengthy and traumatic struggle for independence from Britain, and the shadow of the decades-long spasm of sectarian violence known as the Troubles, which subsided with the Good Friday peace accords in 1998.

Northern Ireland wants to move forward. But 25 years after the Good Friday accord celebrated by Clinton and Biden, many are mired in a painful past.

“From our history we know what it means,” Simon Harris, the taoiseach, or prime minister, told reporters in Dublin. “A two-state solution is the only way out of the generational cycles of violence, retaliation and resentment, where so many wrongs can never make a right.”

In making their announcements, all three governments — Ireland, Spain and Norway — were at pains to express support for Israel’s existence, and revulsion over the Hamas-led attack on Oct. 7 that killed about 1,200 people and triggered the war in Gaza. Still, the recognition amounted to an unmistakable voicing of dismay over the war’s immense civilian toll.

“This recognition is not against anyone — it is not against the Israeli people,” said Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sánchez. He called it “an act in favor of peace, justice and moral consistency.”

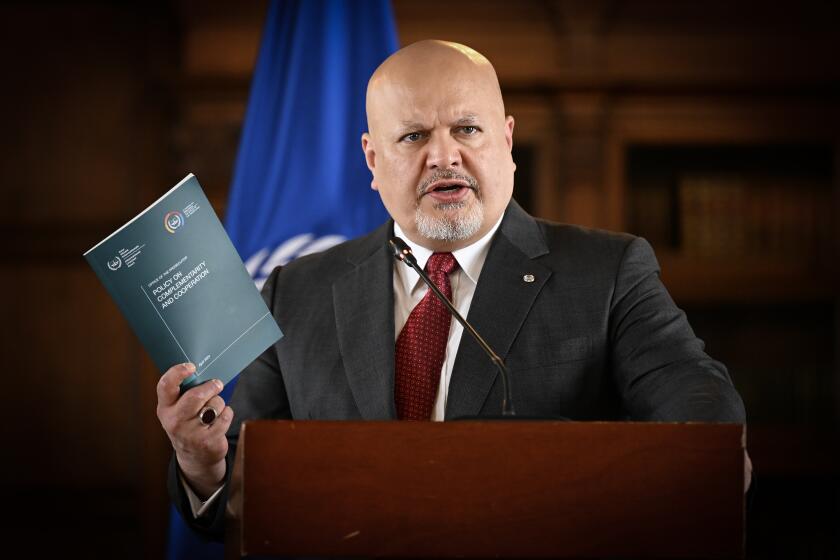

A prosecutor asks the International Criminal Court to issue arrest warrants for the Israeli prime minister, an aide and Hamas leaders

Israel, though, was infuriated by the second international episode this week to deepen its isolation. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the recognitions a “reward for terrorism.”

The announcements came on the heels of Monday’s news that the International Criminal Court’s lead prosecutor was seeking arrest warrants for five senior Israeli and Hamas officials, including Netanyahu, over potential war crimes and crimes against humanity related to the current conflict.

Most Western European states accept the court’s jurisdiction, although the United States and Israel do not.

The recognition announcements were welcomed both by Hamas and by its rival, the Palestinian Authority. Israel, however, recalled for consultations its ambassadors to Ireland, Spain and Norway.

Palestinian statehood recognition has already been extended by at least 140 of about 190 countries represented in the United Nations, but Wednesday’s push represents an impetus not seen for years within Europe.

Five of the earlier EU announcements date back to 1988, together with that of Cyprus, which extended recognition before joining the bloc. Sweden recognized a Palestinian state in 2014.

With the war in Gaza now in its eighth month, the U.N. General Assembly this month approved Palestinian “rights and privileges” that were seen as a prelude to a potential vote to grant full membership. Currently, the Palestinian Authority has observer status.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.