Obama argues against use of force to solve global conflicts

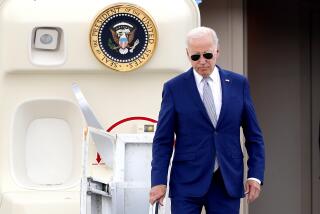

Reporting from Manila — On the final stop of his weeklong Asian tour, President Obama on Monday answered the question that has dogged him all along the way: Has he gone too far in reducing America’s historical role in global security?

The president, who rode into office on a wave of antiwar sentiment, responded with a challenge of his own: Haven’t people heard of Iraq and Afghanistan?

“Why is it that everybody is so eager to use military force after we’ve just gone through a decade of war at enormous costs?” Obama said at a news conference. “And what is it exactly that these critics think would have been accomplished?”

Policy problems in many parts of the globe made headlines throughout the trip, which ends Tuesday.

In Syria, much of the country is a shambles after three years of war and President Bashar Assad, who Obama has said “must go,” is tightening his grip. Russia has annexed Crimea from Ukraine and massed tens of thousands of troops along Ukraine’s eastern border. And as Obama has attended state dinners, given speeches and held meetings in Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines in the last week, North Korea has threatened another nuclear test.

Asian allies have tried to gauge the Obama administration’s willingness to protect them from China’s growing economic and military might.

The president’s aides have scrambled to put things in simpler terms. “Don’t do stupid stuff” is the polite-company version of a phrase they use to describe the president’s foreign policy. The mantra, meant to contrast with the policies of George W. Bush, helps explain Obama’s measured approach, one that critics say is passive and ineffective.

Obama has been willing to launch clandestine operations against suspected terrorists in Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia and elsewhere. He took a chance on the raid in Pakistan that killed Osama bin Laden. His opening to Iran may eventually end decades of hostility, but still faces daunting odds and could lead nowhere.

However, he has resisted embarking on grand projects or laying out a single, sweeping doctrine. His aides tend to evaluate conflicts one by one, in most cases settling for small steps.

Increasingly, Obama argues that his foreign policy record will have to be judged historically. At a news conference Friday in Seoul, he repeatedly appealed for people to take the long view.

That caution has unnerved some of America’s closest allies, as well as domestic critics.

Japanese officials openly wondered, before Obama arrived in Tokyo last week, whether the White House would intervene on their behalf if China seized disputed islands in the East China Sea, just as Russian forces had seized Crimea.

Obama said the U.S. would “absolutely” honor its defense treaty with Japan.

Similarly, Obama’s decision in September not to follow through on his threat to bomb Syria for using chemical weapons made allies in Europe and Asia wonder whether war weariness was devaluing U.S. security promises.

The White House responds that the threat worked: Assad’s government has surrendered more than 90% of its chemical weapons arsenal and infrastructure to international monitors.

But the Syrian civil war continues, Islamic extremists are a strengthening part of the rebel movement, and instead of leaving the scene, Assad announced Monday that he would run for reelection.

Saudi Arabia, a staunch U.S. ally for decades, has questioned whether Washington would protect it from Iran, Syria and their proxies. The Saudis suggested they might turn to other great powers for support if the U.S. hedged on its commitments.

Polls indicate Obama’s approach is broadly shared by the American public, which believes that the United States has gained little from its long military commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Those who want him to act more forcefully include not only Republicans but also liberal internationalists and some members of his staff.

Although Obama views the conflict over Ukraine as a second-tier issue, some administration officials consider it a grave threat to the post-Cold War order. The White House on Monday announced another round of modest sanctions, against two dozen Russian officials and companies, to try to pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin to stand down on Ukraine.

Republican Sens. John McCain of Arizona and Bob Corker of Tennessee have warned about what they say is a growing perception of U.S. weakness. McCain has called Obama’s foreign policy “feckless.” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) calls the president “weak and indecisive” and says his approach invites aggression.

Obama is right to resist reacting to each short-term crisis with threats of force, said Bruce Jones, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of “Still Ours to Lead,” a book about U.S. leadership in a world with many new, rising powers.

“I think he’s wise to do it, but he’s not managed to communicate an effective narrative,” Jones said. “At one level he’s right, and at another level he’s unsatisfying.”

The Syrian civil war is perhaps the most hotly debated foreign policy problem.

On Monday in Manila, Obama argued his case, mimicking and answering his Republican critics.

“I would note that those who criticize our foreign policy with respect to Syria, they themselves say, ‘No, no, no, we don’t mean sending in troops,’ ” Obama said. “Well, what do you mean? ‘Well, you should be assisting the opposition.’ Well, we’re assisting the opposition. What else do you mean? ‘Well, perhaps you should have taken a strike in Syria to get chemical weapons out of Syria.’ Well, it turns out we’re getting chemical weapons out of Syria without having initiated a strike. So what else are you talking about? And at that point it kind of trails off.”

Obama similarly maintained that he had few real options to stop Russia from moving on Ukraine.

“Do people actually think that somehow us sending some additional arms into Ukraine could potentially deter the Russian army?” he asked. “Or are we more likely to deter them by applying the sort of international pressure, diplomatic pressure and economic pressure that we’re applying?”

Still, as Obama has toured Asia, foreign leaders and audiences have pressed him for assurances that the U.S. has their backs. His promise that it does came with calls for peaceful resolution of conflicts.

In Manila, Obama applauded the Philippine government’s decision to pursue international arbitration concerning its dispute with China over a scattering of rocks and reefs, the Spratly Islands. Together they form less than 1.5 square miles of land spread over 164,000 square miles of sea.

Whatever actions the U.S. takes, Obama said, it shouldn’t be because “somebody sitting in an office in Washington or New York thinks it would look strong.”

Strong alliances and partnerships “may not always be sexy,” he said. “That may not always attract a lot of attention, and it doesn’t make for good argument on Sunday morning shows.

“But,” he said, “it avoids errors.”

kathleen.hennessey@latimes.com

Parsons reported from Manila and Hennessey and Richter from Washington.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.