In Brazil, where violent deaths of LGBTQ people are on the rise, a shelter opens for youth

Reporting from SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Tuesday morning yoga is canceled.

The call comes 15 minutes before it was supposed to start, leaving Iran Giusti no time to let students know their teacher won’t make it to the Casa 1 community center in downtown São Paulo for the 10 a.m. class.

As he hangs up the phone, two students walk into the large, high-ceilinged former garage where Giusti is working, his laptop sitting on a long wooden tabletop supported by trestle-style legs.

Casa 1, a home for LGBTQ youth kicked out by their families because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, opened the doors of its community center in September, but the original house, just up the street and around the corner, celebrated its first anniversary on Jan. 25.

It was much needed. While São Paulo is known for having the largest Gay Pride Parade in the world and same-sex marriage has been legal in Brazil since 2013, violent deaths of LGBTQ people in the country hit an all-time high last year, when at least 445 Brazilians died because of violence related to homophobia, according to the watchdog Gay Group of Bahia. Of that total, 387 were homicides and 58 were suicides.

“Sorry, there won’t be a class today,” Giusti says to the young men coming in through the side door from the center’s main lobby area. Giusti’s three dogs circle the room, tails wagging as they walk out the open garage door to the front gate and back again.

One of the students walks across the room and hands Giusti a white plastic grocery bag filled with toilet paper, toothpaste, soap and shampoo.

“I brought some donations, so it was still worth the trip,” he says with a smile.

Giusti thanks him and gives him a hug.

Giusti sets the bag next to his feet and looks back at his computer. Even with the garage door open and two fans spinning at maximum speed, the summer heat is stifling. He’s trying to access Casa 1’s books to see what he has to work with this month, but the internet is out in the whole neighborhood.

“We run this place just like any other Brazilian household: one month you pay the gas bill, the next you pay the lights,” he says with a laugh. “Then at least nothing gets shut off.”

The second floor of Casa 1’s red brick building was originally expected to house eight people, but Giusti had to make room for 12 in its first week. Now, Casa 1 is home to up to 20 at a time. The gender identity of residents tends to be split down the middle: 50% transgender, 50% cisgender (someone whose gender identity matches their gender at birth). In its first year, 78 people between the ages of 18 and 25 passed through its doors, staying for up to four months each. While there, finding permanent housing and employment, finishing education, and taking care of both physical and mental health are made priorities. Most of the volunteers at Casa 1 are healthcare professionals and educators who help residents get back on track when they have nowhere else to go.

Below the residence on the first floor are three spaces that are open to the public: a library, a gallery showcasing LGBTQ art, and a clothing shop that donates the items it receives to people who are homeless.

Workshops and courses used to take place here, but the space was too small, leading Giusti to open Casa 1’s nearby community center. While residents are given first pick, the free activities are also open to the public, and many of the center’s neighbors come to take classes in subjects as varied as yoga, sewing, English and computer basics.

It’s just before 2 p.m. when Reinaldo da Silva Freitas Jr. walks into the space where the morning’s yoga class was supposed to take place. He spent his morning handing out resumes and walked from his home at Casa 1 to the community center after having a lunch of roast beef, rice, beans and salad left over from an event the day before.

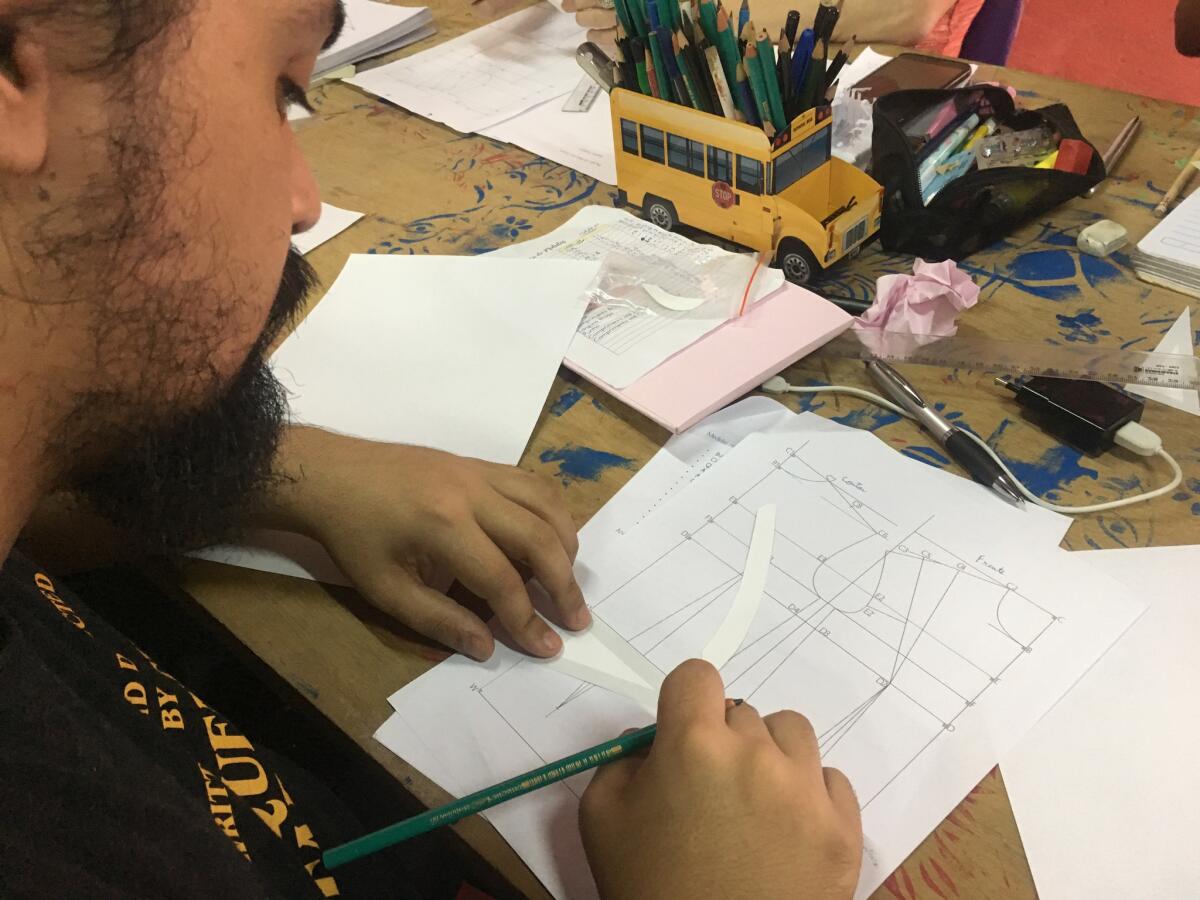

A second wooden table has been set up parallel to the first to make room for this afternoon’s sewing class. Two students are already sitting across from each other at one. Freitas pulls a white plastic chair from a stack in the corner and sits next to Andrea Ferrara, who is talking to Max Milliano Melo. She waves to him.

“Hey Reinaldo, did you remember to bring your measurements?” she asks.

He pulls a notebook from his bag and takes out a small sheet of paper.

“I thought I forgot them, but they’re here,” he says.

Other students trickle in as the three wait for their teacher to arrive.

“How long have you been at Casa 1 now?” Ferrara asks.

“Since the end of November, so just over a month,” Freitas says.

Freitas is 19 and Casa 1 is the fourth home in his tumultuous life. His mother died when he was a baby and his father sent him to live with family friends in a rural area of Mato Grosso do Sul state. When he was 7, his father returned to send him to São Paulo to live with a woman he was told was an aunt, although he would later learn she was not a relative. Despite that, he came to regard her as his mother, someone he could trust to accept him when he told her about his sexuality. Instead, she gave him two days to get out of her house.

“It’s been great so far,” he says to Ferrara and Melo of his time at Casa 1. “All I need now is a job. Then I can save some money so I can rent a room and go to college one day. I want to study fashion.”

Just then, their sewing teacher, Nawira Scarano, comes through the open garage door.

“Sorry I’m late, everyone.”

She puts her bag down on the other table and explains that today’s class will be about the theory of pattern making.

“I’m going to show you the hard way so that everything else you do going forward will seem easy.”

As she hands out mini French curve templates she’s made out of paper, Freitas swipes down on his cellphone screen with his thumb.

“Reinaldo, get off that phone,” she says with a smile. “There’s no Facebook in this class.”

“I don’t even have Facebook on here anymore,” he says. “It was way too much.”

“Instagram then. I know how much you love it.”

Freitas grins and puts his phone on the table as Scarano explains the patterns they’ll make will only be half of the garment, a shirt, since the fabric will be folded to make each side identical.

Scarano asks her students to take out the sheets of paper with the measurements they took last week. She circles the table to make sure everyone understands how to do the math to make the pattern.

“Anyone who has a body with curves or who wants pleats at the waist, you can put them in now,” she says. “Unfortunately, when you look up patterns online, they’ll all be labeled as either male or female. Patterns without genders don’t exist yet.”

Freitas practices folding a pleat with a sheet of paper. When he manages to get it just right, he holds it up to show Scarano.

“Nailed it!” he says.

“If we have enough time, I’ll show you a video on construction from Dior,” she says.

“Ah, always with the Dior.”

As they continue to draw their patterns, a student new to the class comments that his father was a tailor and he has French curves at home they can use.

“A tailor?” says Freitas. “So where are all your luxury clothes?”

“At home in my closet,” he says, laughing. “Just like I used to be.”

Langlois is a special correspondent.

To read this article in Spanish, click here

ALSO:

Brazil has seen a wave of inmate riots. The latest one left 10 people dead

Onetime popular president eyed a return to power. Ecuador voters had other ideas

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.