Decades ago, he stole a tree branch. Now he is the Durian King

- Share via

Long before he was the Durian King, Tan Eow Chong was canvassing rural Malaysia for plants he could farm when he stumbled on a roadside stand selling a curiously golden-fleshed variety of the fruit.

The seller, an elderly woman, urged Tan to have a taste, boasting that her durians were the same color as the local sultan’s palace.

Tan took one bite and was transfixed. Apart from the notorious aroma, which is often compared to rotting meat, it was nothing like the fibrous durians with large pits that he grew at home 200 miles away on Penang Island. This one was meatier, creamier and bittersweet — everything a durian connoisseur would want.

“The flesh melted in my mouth,” said Tan, who decided then that he had to grow the durian himself.

The fruit came from a nearby orchard. Tan asked whether he could have a branch to graft onto one of his trees, but the woman shooed away the idea. So that evening he returned with a villager armed with a rifle. At Tan’s instructions, and for pay, the man pruned a footlong branch with a well-placed shot.

Thirty-five years after his heist, Tan is reaping the rewards.

The tree limb provided the genetics for an award-winning durian known as the Musang King, which has become Malaysia’s next cash crop and made Tan’s family durian royalty.

His success, however, came only recently — thanks to his perseverance through hard economic times and a magnate who happened to spark a Musang King obsession in China, a country whose 1.4 billion stomachs have the power to move markets.

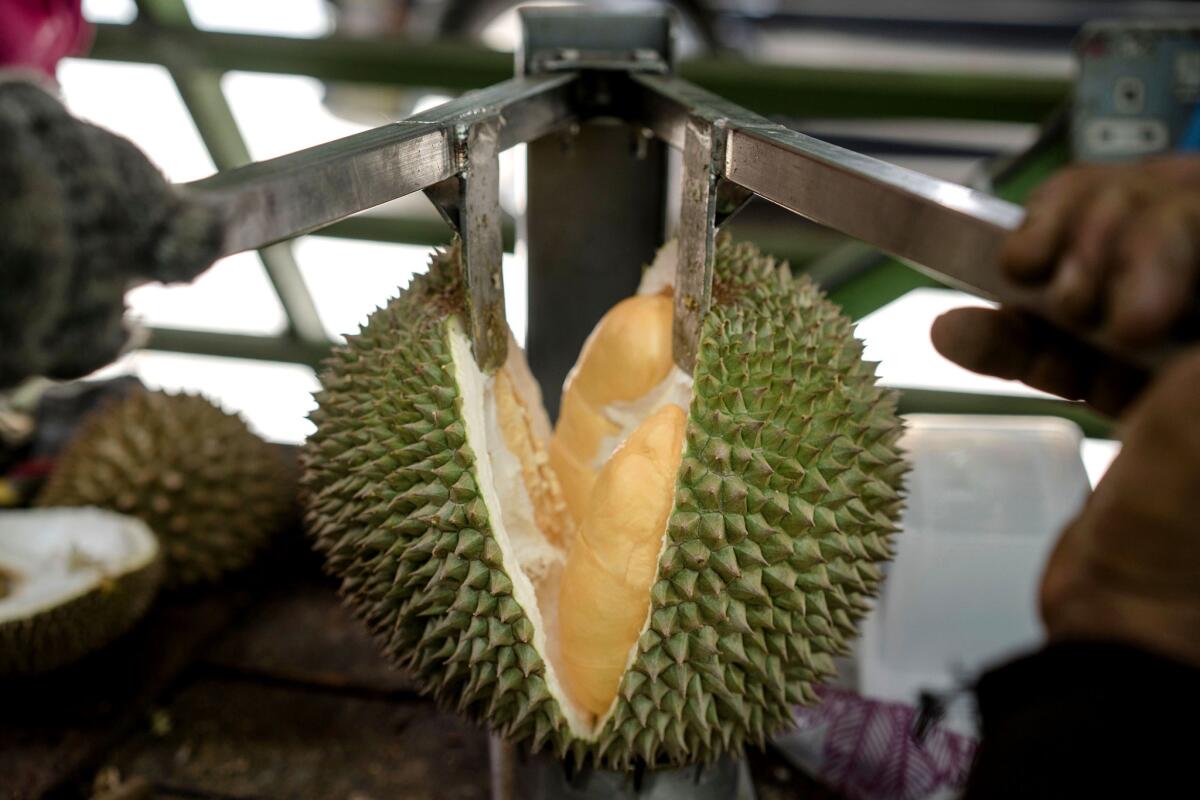

The durian is no ordinary fruit. Its thorny cantaloupe-sized husk looks like a hedgehog crossed with an avocado. Locked inside are lobes of fruit that have the look and texture of foie gras and are usually eaten raw, but can also be mixed with rice or added to pastries.

What defines durian fruit, however, is its overpowering sulfuric scent, which has led to bans from public transportation and the occasional evacuation of buildings. The odor is strong enough to penetrate the fruit’s thick shell. When the shell is cracked open, the scent can buckle a neophyte’s knees. But for the fruit’s admirers, the stench is part of the allure.

“If it doesn’t stink, it’s not durian,” Tan said.

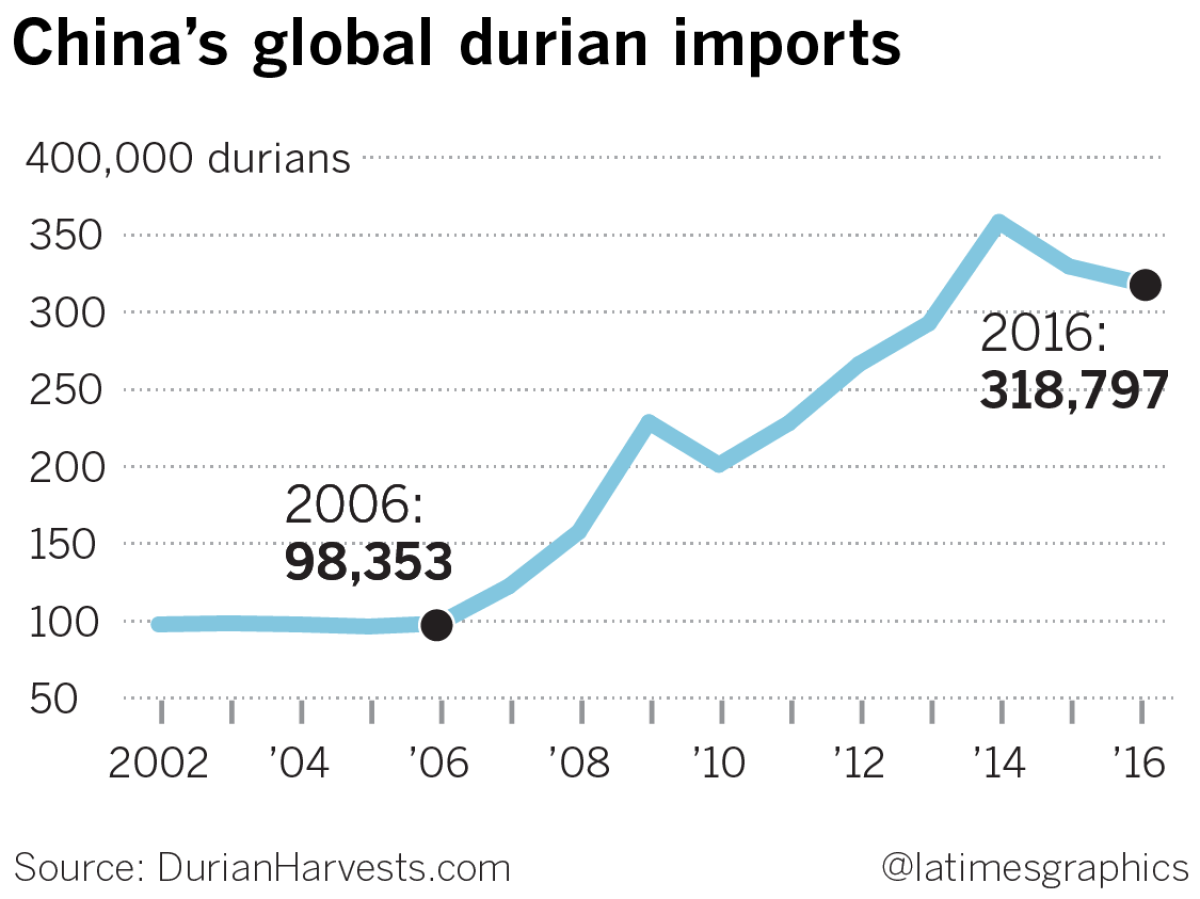

The world’s biggest emerging consumer market appears firmly in favor of the smell. China’s massive unmet demand for durian is the prime reason the Hong Kong consulting firm Plantations International predicts that the global market for raw durian will reach $25 billion by 2030 — up from $15 billion in 2016.

A growing share of that is expected to come from Malaysia, where the fruit is thought to have originated and the average person eats 24 pounds of it each year — far more than anywhere else in world.

Tan, 58, has seen his revenue grow tenfold in the six years since he began exporting durians to China.

Now, among locals on this lush island west of the Malay peninsula, Tan is the Durian King.

The story of how Tan earned his crown begins with his father, a pig farmer from China’s coastal Fujian province. Before migrating to Malaysia in the 1940s, the elder Tan had never seen a durian.

He noticed the fruit growing wild on his property in Balik Pulau, a bucolic corner of Penang, and decided to farm it.

Back then, there was mostly one variety of durian, the Kampung, the Malay word for village. Though still sought after, it is unremarkable compared with today’s hybrid varieties.

Tan learned to farm as a boy in the early 1970s alongside his father. But he didn’t particularly like it and as a young man became a self-described gangster — a dai goh, or big brother in Cantonese parlance — overseeing a band of hoodlums.

By his early 20s, though, he began taking farming seriously after his father explained how he planned to bequeath his farmland one day. Tan’s two brothers would split the family’s coffee plantings and hog farm.

Tan would inherit the durian plantation, a nod to his passion for the Frankenstein science of grafting. The skill allowed him to improve on the Kampung by cross-breeding it with richer and meatier durians he’d occasionally find.

“If it doesn’t stink, it’s not durian.”

— Tan Eow Chong

It was the technique he used when he brought back his prized limb from behind the roadside stand in the northeastern state of Kelantan and joined it to a mature tree.

It took Tan three years for the grafting to bear fruit and two more years of plantings to come up with a durian he was willing to sell.

He called it Rajah Kunyit, Malay for Turmeric King, on account of the meat’s bright yellow hue. Growers on the Malaysian mainland developed an identical hybrid, but called it the Musang King, which means Mountain Cat King. The latter name stuck.

The new variety brought Tan a modicum of fame, but at only $1 for about 2 pounds, no fortune.

The market for Malaysian durian was mostly domestic, providing little opportunity for major growth. It was difficult to compete with Thailand, the world’s biggest exporter of durians, mostly its ubiquitous Monthong, or Golden Pillow.

Tan took full control of his family’s durian business after his father died in 1998, just as the market for the fruit was about to enter a deep, multi-year slump.

Meanwhile, another crop was taking off: the palm oil plant.

Used in everyday products such as candy bars and cosmetics, it accounts for half the agricultural economic output of Malaysia, the world’s No. 2 producer behind Indonesia. Viewed from above, the cylindrical trees organized in equidistant rows can make great swaths of the country look like it’s made of Legos.

Combined with government incentives, the crop has lifted millions of rural dwellers out of poverty — and become a significant contributor to climate change as the country’s dense rain forests, which absorb carbon dioxide, were cleared to create palm plantations.

In 2005, Tan seriously considered ripping out his durian trees and joining the trend.

But he had no experience growing palm or passion for the plant and decided to stick with what he knew best.

“My life has always been with durians,” he said.

Luckily for Tan, Stanley Ho, a legendary casino tycoon from the Chinese territory of Macao, also happens to be a durian devotee.

In 2010, he sent a private jet to Singapore to pick up 88 Musang Kings from a seller there. He wanted 98, but stock was low.

Ho reportedly gave away 10 of his beloved fruits to an even richer billionaire, Hong Kong developer and investor Li Ka-shing.

The story, which was originally reported by a Chinese-language newspaper in Malaysia called China Press, quickly reached China.

Soon 4.5-pound Musang Kings were selling for up to $60 each on Chinese e-commerce sites such as Taobao.

Durians are prized in China, not only for their unique flavor — as sweet as ripe banana and simultaneously as bitter as raw garlic — but also supposed health properties. Nursing mothers are encouraged to eat the fruit. And it’s believed to keep you warm during winter.

No variety is more prized than the one Tan pioneered.

“The Musang King is my favorite,” said Teh Bin Tean, a Singaporean researcher who has studied the durian genome. “Don’t try it first because the rest is all downhill.”

Tan seized on Chinese demand in 2013 by finding a distributor in China and ways to flash freeze the freshly picked fruit with nitrogen for shipping.

Since then, the family’s durian plantings have increased to 1,000 acres from 80. Last year, the business exported 1,000 tons of the fruit to China.

“We couldn’t dream business would go so high,” said one of Tan’s sons, Tan Chee Keat, who has been learning the business.

Now corporations are looking to cash in on China’s latest culinary fixation.

Major Malaysian palm oil interests such as the publicly traded IOI Group and the state-owned Federal Land Development Authority are exploring durian planting, according to an industry official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to disclose his talks with the organizations. Neither responded to requests for comment.

Their interest comes at a time when global palm oil prices have declined steadily because of new regulations and boycotts.

Environmental groups hope any durian boom doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the palm oil industry and exacerbate the depletion of forests.

“Durian has always been one of our favorite crops, but we’ve got to have a balance,” said Sophine Tann of the Malaysian environmental protection group PEKA. “With rising demand from China we’re worried they’ll say ‘Let’s get rid of all our forests for durian.’ Do we need to be the world’s supermarket?”

In 2002, when Chee Keat was 11 and the family farm was struggling, his father made him stand in the center of a plantation to get used to the mosquitoes, which are often so numerous they can be confused for pollen.

“I was a blood donor,” joked the younger Tan, who wanted no part of the farming life and wanted to be a paleontologist.

Years later, the mosquitoes no longer bother him. All that time on the hilly farms has inured him to boars, monkeys, eagles, flying squirrels, deadly snakes and other critters that live there.

“Don’t worry,” he told a Times reporter when a crimson and black snake appeared a few feet away. “That one is only a little bit poisonous. It will make you pass out for a day. You get to rest.”

Tan Chee Keat came to relish durian farming after discovering a passion for grafting, much like his dad did. If all goes as planned, the younger Tan will share the family business with his two brothers.

On the cusp of the peak durian harvest, which starts each June, he often sleeps in a hammock on the family plantations, guarding ripening fruits from thieves. Durian farming is a cutthroat business. Rivals are suspected of poisoning some of his experimental durian trees.

His biggest fear, however, is that someone steals a branch from one of his new hybrid trees, just like his father did so many years earlier. Tan Chee Keat is developing a durian that has an even smoother texture than his father’s Musang King. He hasn’t named it yet, but he suspects it could result in change on the family throne.

With this, he said, “a new king” will be born.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.