Here’s what to expect around the world in 2019

No one could have predicted half the major global developments of 2018. President Trump sitting down with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un? French workers rising up by the hundreds of thousands, all wearing Day-Glo yellow vests? The world transfixed by the rescue of a dozen Thai boys in a cave?

So we exercise caution here in casting an eye forward to likely global trends in 2019. The Times’ network of global correspondents takes a look at what’s looming in nine countries around the world in the new year:

China

The U.S.-China trade war has brought China’s economic slowdown into sharp relief. Chinese authorities will need to address heavy debt, weak growth and a loss of consumer confidence in the coming year. How they do so depends in part on the trade talks with the U.S., which are on a deadline for March 1.

Trust is deteriorating in the meantime, with cybersecurity concerns, accusations of espionage and detention of civilians on both sides (Canada has also been drawn into the fray). China sees U.S. policy as unpredictable, decided by a White House seeming at odds with multiple parts of its own government.

China, on the other hand, seems to be on a fixed path of consolidating Communist Party control. Xi Jinping’s recent speech on the 40th anniversary of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms confirmed that, with its emphasis on party correctness and no mention of new reforms. China’s focus on “maintaining stability” is likely to drive domestic policies as well, with continued restriction of religious minorities, civil society, labor unions and the press.

— Alice Su

Nigeria

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, goes to the polls in high-stakes elections on Feb. 16, a vote that comes as the country grapples with a volatile economy, rising poverty and unrelenting insecurity as the militant group Boko Haram holds its ground.

The incumbent, President Muhammadu Buhari, is a former military leader who vowed to defeat Boko Haram when he was elected in 2015; but the militant Islamist group, while weakened, continues to stage deadly attacks in the nation’s northeast as under-resourced troops grow weary.

With more than 70 presidential candidates expected to run, Buhari’s biggest competition in next year’s polls will be opposition leader and former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, now a successful businessman who promises to alleviate poverty and create jobs.

It’s expected to be a close contest that observers say could be a turning point for one of Africa’s most powerful nations. If the vote is fair and peaceful, it could solidify Nigeria’s place as one of the continent’s strongest democracies. If election day is instead marred by fraud and violence, the country risks sliding into deeper instability — and dragging its neighbors down with it.

— Krista Mahr

India

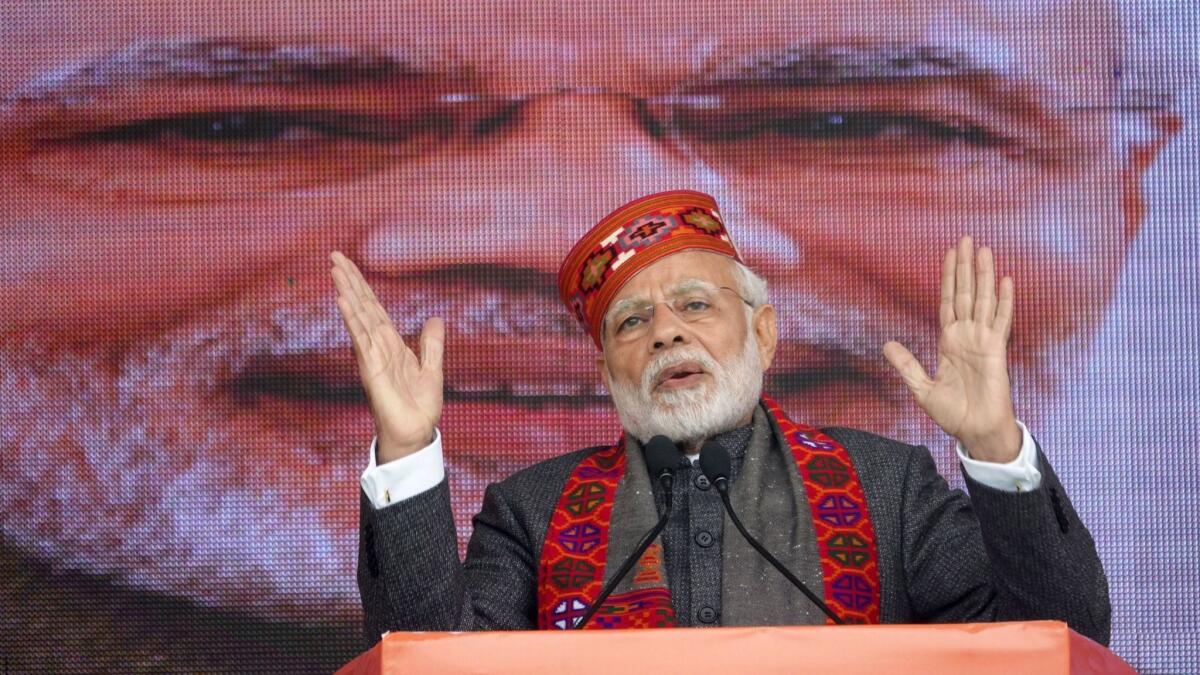

He is India’s most charismatic politician in a generation, and for 4½ years he has ruled with a swagger that captivated Indians who have long believed their country wasn’t taken seriously enough on the world stage. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s hype seems to have caught up with him.

His 2016 decision to cancel the two most valuable currency notes looks increasingly like a colossal blunder. Relations with nuclear-armed rival Pakistan are at an ebb. And Modi has been silent as partisans and officials of his Hindu nationalist party are implicated in hate crimes against minority Muslims.

This month, Modi’s party lost control of three state assemblies, portending a tougher-than-expected battle for him to retain power in nationwide elections in May. His opponents are divided and lack a leader of his stature. But even if Modi wins again, his allure as a statesman and reformer has faded.

— Shashank Bengali

Israel

The new year promises legal, political and security challenges for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who is facing reelection in 2019.

More than any other foreign leader, Netanyahu tethered his nation’s fortunes to President Trump, a strategy whose wisdom was called into doubt following the surprise announcement of the withdrawal of American troops from Syria, where they have supported Israel’s efforts to counter Iranian entrenchment.

In addition, Netanyahu’s indictment in several corruption cases seems inevitable. After more than a year of investigation, the police and the state attorney recommended he be charged, and leading jurists believe there is no realistic possibility of avoiding prosecution.

At year’s end, Netanyahu was forced to confront the fact that he could no longer hold together his ruling coalition. He dissolved parliament and called new elections for April 9.

— Noga Tarnopolsky

Syria

When President Trump announced his pullout from Syria this month, he reaffirmed a growing sense that the civil war raging through the country, which has killed hundreds of thousands and made Syria a byword for suffering, is finally winding down.

Yet for many of the belligerents, the war is not over. The government of President Bashar Assad, at its strongest since the conflict began in 2011, insists it will again control every inch of Syria. It has ousted its rebel adversaries from almost all their areas. The announcement by the United Arab Emirates that it was reopening its embassy in Damascus sent a signal that even Assad’s former foes consider him the victor.

But it now faces a more complicated challenge in Turkey, with much of north Syria in its grip. And in the desert, Islamic State, defeated but not vanquished, awaits the opportunity to rise again.

— Nabih Bulos

Mexico

If Mexico is indeed facing a fundamental “transformation” — as new President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has vowed — then 2019 should be the year when the country begins to head in a more positive direction.

Lopez Obrador took office on Dec. 1 for a six-year term, becoming Mexico’s first avowedly leftist president in a generation. His grandiose campaign promises included pledges to reduce soaring crime, eliminate long-ingrained corruption, address deep social inequalities and spur the country’s sluggish economy.

It is a sweeping agenda. Many are pessimistic that the new administration can pull it off — despite effective majorities in both houses of the Mexican Congress. The business community remains leery of Lopez Obrador’s populist pronouncements. He does appear to have charmed President Trump. The two populists from different ends of the ideological spectrum seem to get along well, at least for now.

His biggest challenge will be fulfilling newly stirred hopes that Mexico can be a better place for its citizens. Expectations are high.

— Patrick J. McDonnell

Koreas

After a year of historic breakthroughs and celebratory photo ops, the Korean peninsula heads into 2019 in something of a waiting game: Will North Korea take meaningful steps to denuclearize?

That question is complicated by the fact that there’s disagreement on what “denuclearization” even means — North Korea’s state-run news agency published a statement this month contending it meant not only its relinquishing of nuclear weapons but also the removal of the U.S. arsenal in the region.

Although talks between the U.S. and North Korea have stalled, South Korea’s liberal government is trying its best to continue engaging with its neighbor to the north while not running afoul of its U.S. ally or of economic sanctions designed to pressure North Korea. Projects to link up railways and roadways, jointly host the Olympics in 2032 and provide humanitarian aid are all underway. Those efforts may be threatened in the new year by criticisms within South Korea of President Moon Jae-in as being unable to fix domestic economic problems while his attention is consumed by the North.

On the North Korean side, experts say it remains to be seen whether strict economic sanctions are making a significant dent on a domestic economy that has been much improved under Kim Jong Un’s rule. If they are, it could force North Korea back to the table.

— Victoria Kim

Russia

Russian President Vladimir Putin may be facing one of the most serious political challenges of his career in 2019. But this time, the Kremlin leader’s obstacles aren’t coming from abroad by way of sanctions or diplomatic standoffs. Putin’s biggest problem in 2019 may be his own people’s anger and frustrations.

Putin’s approval ratings dropped significantly after he introduced controversial pension reforms this summer. Thousands of Russians took to the streets to protest the move, saying that by raising the retirement age, the Kremlin was planning to fund depleting budget revenues at the people’s expense. Public opinion polls — which the Kremlin is said to watch very closely — showed that only 39% of Russians surveyed in October considered Putin a politician they could trust. That’s a 20-percentage-point drop from the response to the same question a year ago.

Dissatisfaction rippled across the country. In fall elections, Putin’s ruling party, United Russia, lost several local races for the first time, signaling that the Kremlin may be losing power in the regions. Meanwhile, economic growth has almost flatlined, inflation is rising, and incomes are stagnant. Put together, it could be a perfect storm for larger protests against the Kremlin. But that, some observers warn, could be an impetus for Putin to crack down harder on dissent.

— Sabra Ayres

Britain

After decades of membership and years of fraught debate, 2019 is expected to be the year that Britain finally leaves the European Union.

Brexit is scheduled to formally take effect March 29, but given how challenging the negotiations have been to date, nothing is yet guaranteed. The first three months of the year will be critical to ensuring that timeline goes according to plan. As soon as the holidays are over, British Prime Minister Theresa May will summon her Cabinet back together in preparation for lawmakers voting on her Brexit divorce deal in the week of Jan. 14.

The deal has already been approved by the other 27 EU members but also needs to win passage in the British Parliament. If it passes, the way ahead looks clear for May, who has vowed to honor the results of the 2016 referendum, which saw 52% of the country vote to leave the EU.

If it fails, the path ahead for May, the country and Brexit is far from certain and calls will grow louder for a second referendum or a general election in order to put the Brexit decision back into the hands of the people.

— Christina Boyle

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.