Could Turkey’s president be in trouble? He faces a stiff challenge in Sunday’s election

- Share via

Reporting from Istanbul, Turkey — The stakes for Turkey could not be higher.

Voters on Sunday will cast ballots in a presidential election that could return President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to a second term in office. But the election will determine far more than that.

Should Erdogan win, his victory will cement a sweeping constitutional revision that critics fear will create something close to a dictatorship. Erdogan says the changes would merely rid Turkey of a “bureaucratic oligarchy” that is keeping him from turning the country’s economy around.

There are signs, however, that the Turkish president — who has ruled the country in one form or another since 2003, when he became prime minister — may have overreached.

Polls show Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party and its allies in parliament falling slightly short of the 50% needed to control the legislature.

Erdogan himself is polling just under the 50% needed to win the presidential contest outright, and the opposition is hoping to pool supporters behind a single candidate who could defeat him in a runoff that would be held on July 8.

“The opposition’s goal is to maximize turnout among their voters to prevent a first round victory for Erdogan,” said Aykan Erdemir, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a former lawmaker with the Republican People’s Party, Turkey’s largest opposition party.

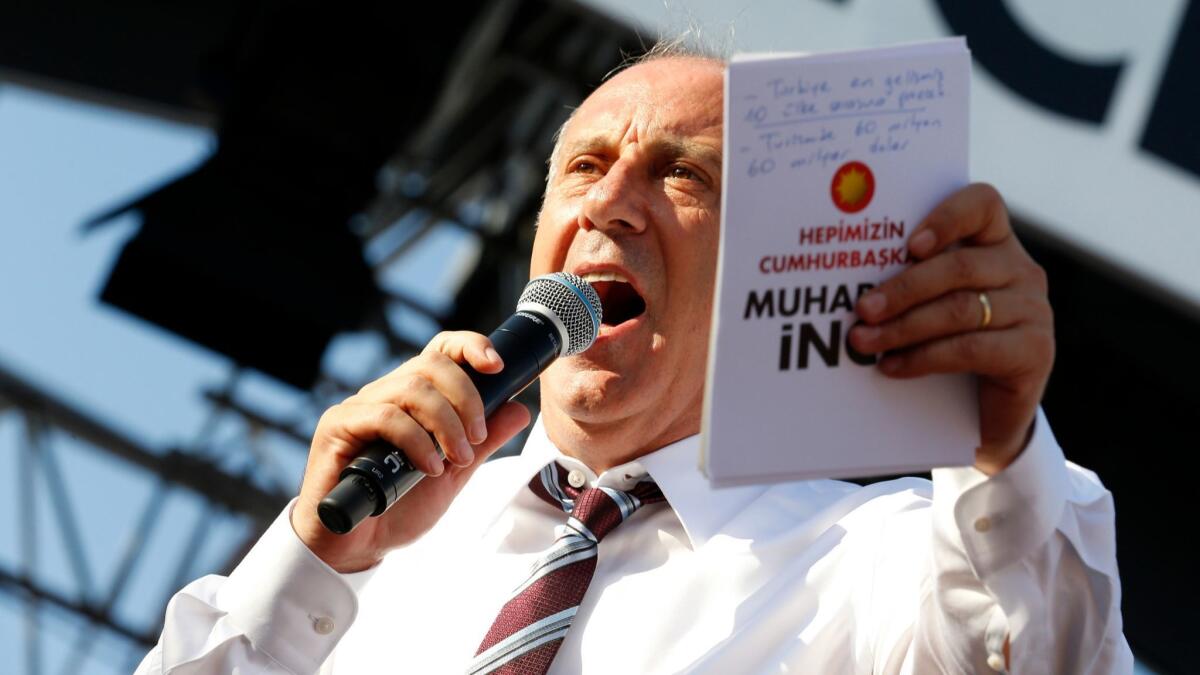

Five major opposition parties have formed a tacit alliance against Erdogan. Muharrem Ince, 54, who has served in parliament with the Republican People’s Party since 2002, is expected to win 20% to 30% of the vote, making him the most likely to face Erdogan in a runoff.

The other four opposition parties have indicated they would support Ince if he reaches the second round, and the former physics teacher has campaigned on an inclusive platform that could bridge the traditional religious and ethnic divides in the country.

“I will be president for all of you,” Ince said at a rally in the coastal city of Izmir that drew hundreds of thousands of supporters on Thursday. “I will unite the country.”

Sunday’s election will occur 17 months ahead of schedule — part of a plan by Erdogan to ensure that the new constitutional system can come into effect. Voters will select from among six candidates for president, and eight parties to represent them in the 600-seat parliament.

Erdogan has long expressed frustration over the country’s parliamentary system, saying the need to form coalition governments, and an imbalance of power between the legislative and executive branches made it difficult to meet the demands of the voters who put him in office.

Last April, a slim majority approved the package of constitutional amendments that transformed Turkey, which has been governed by a multiparty parliamentary system since 1950, into a presidential system.

Erdogan’s supporters say it is akin to the system in the United States, but critics say it lacks checks and balances.

Energized by polls showing that victory may be within their reach, opposition parties are hoping to unseat Erdogan and roll back a constitutional system that they say would resemble a dictatorship.

“If parliament is under majority control of the opposition, it may work as a watchdog, because it can issue new laws to undo the presidential decrees,” said Levent Korkut, a constitutional lawyer and lecturer at Istanbul’s Medipol University. But if parliament and the president can’t get along, he added, “a political crisis may occur.... It is a totally blurred era we are entering.”

Under the new system, there will still be the traditional three branches of government — judiciary, executive and legislative — but the president will be endowed with powers that could make him the only real power in the country.

The president won’t need parliament’s approval to appoint a Cabinet, and could issue executive decrees with the power of law.

The country’s top courts could rule such decrees unconstitutional if they are found to infringe on fundamental rights, but under the new system, the president will exercise expanded control of the judiciary as well. He will directly appoint 12 of 15 members of the Constitutional Court to 12-year terms, and six of 13 members of the body that appoints judges and prosecutors nationwide.

Opposition candidates have pledged to undo the constitutional changes, but that is an unlikely scenario, Korkut said. Amending the constitution would require a two-thirds majority in parliament, or slightly fewer to put the question to another referendum.

Ince has also offered a stinging commentary on Erdogan’s style of governance, touching on the country’s faltering economy, the war in Syria and the government’s handling of the aftermath of a coup attempt in July 2016.

More than 50,000 people, including hundreds of journalists, are in prison awaiting trial on terror charges, and 150,000 public sector workers have been sacked for alleged ties to the coup plotters.

If elected, Ince has pledged to immediately lift a state of emergency in place since the coup attempt, release journalists and reinstate public sector workers who have not been charged in court.

“Erdogan is a tired, passionless man. An arrogant man looking down at the people,” Ince said at a rally in Izmir, a city on the Aegean Sea in western Turkey. “He’s a man without dreams.”

As Ince spoke in Izmir, Erdogan’s presidential plane was landing at the construction site of a new $10-billion airport in Istanbul that will become the world’s largest when it opens in October.

Standing before a giant television screen, Erdogan presented a slide show to reporters explaining how the new presidential system would work.

“The new system does not undermine democracy or the fundamental nature of the republic, but on the contrary, it strengthens it,” Erdogan said, explaining how he would eliminate unnecessary government departments and bring them under the president’s control.

“We have studied our own history and models in the world,” he said. “Our problem seems to be different from other countries.”

Under Erdogan, Turkey has become the world’s 17th-largest economy, but the Turkish lira has lost 20% of its exchange value so far this year, and the private sector has struggled to keep up with payments on foreign loans that are calculated in dollars and euros. Opposition parties have made inflation, which stands at 12%, a central part of their campaign, as the price for basic produce has skyrocketed.

Potatoes cost four times what they did a year ago; onions, five times as much.

“For the first time, one kilogram of onions costs more than a dollar in Turkey,” Ince said at a rally in Istanbul. “There is a big problem in the economy if this is happening.”

In Istanbul, the country’s largest city, flags and banners of political parties are strung across streets, and buses emblazoned with portraits of candidates criss-cross the city, blasting campaign songs.

“We trust Erdogan, and I am going to vote for him because I want him to be able to do more for us,” said Ahmet Ugur, a university student and first-time voter, at a march down central Istiklal Street on Wednesday afternoon.

Supporters chanted pro-Erdogan slogans and held up placards with messages that might well have been endorsed by the opposition as well: “We are far from being tired, and there is much more work to do.”

Farooq is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.