Turkey lifts state of emergency after two-year purge, but will anyone even notice?

Reporting from Istanbul, Turkey — A two-year state of emergency during which thousands were jailed or stripped of their livelihoods was lifted early Thursday, buoying the hopes of some that a time of repression and stifled free speech in Turkey was at an end.

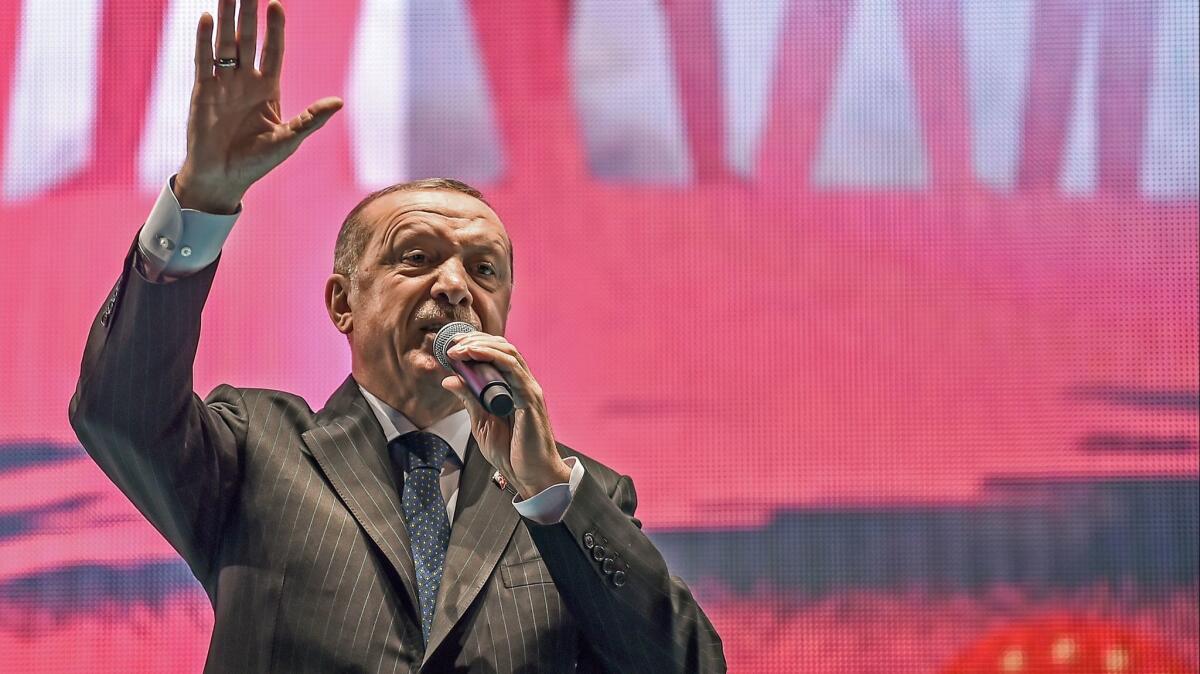

Opposition leaders and human rights activists, however, cautioned that ending the state of emergency could be largely cosmetic and that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was likely to continue flexing his extraordinary powers in an ongoing crackdown on dissent.

“Over the last two years, Turkey has been radically transformed with emergency measures used to consolidate draconian powers, silence critical voices and strip away basic rights,” said Fotis Filippou, deputy Europe director of Amnesty International. “Many will remain in force following the lifting of the state of emergency.”

Turkey imposed the state of emergency on July 20, 2016, five days after a failed coup left 250 people dead. Armed with the new powers, the government went after a religious group it believed was behind the attempted coup. The group, led by Fethullah Gulen, a cleric who now lives in the U.S., was declared a terrorist organization by Turkey.

Since then, more than 77,000 people have been charged with terrorism-related offenses, most accused of being followers of Gulen, or suspected of having ties to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party. Among them are hundreds of journalists, police officers, civil servants and some of the country’s top prosecutors and judges. Scores of news outlets and hundreds of nongovernmental organizations have also been shut down during the state of emergency for unspecified ties to terrorist groups.

Turkey’s Constitutional Court ruled last year that the emergency decrees could not be challenged in court. Originally meant to last only three months, the state of emergency was extended seven times.

In addition to those in prison, more than 150,000 public sector workers were fired in emergency presidential decrees. In addition to being barred from working in government offices or public schools or universities, the workers were stripped of their Turkish passports and their names were published in official documents, a public shaming that human rights advocates call “civil death.”

The last such decree, issued July 8, listed 18,632 people who would face such extreme punishment, including nearly 9,000 police officers, for unspecified links to groups that “act against national security.”

The government formed a special commission to review those who were stripped of their jobs and passports, but few such decisions were overturned.

“The end of the state of emergency does not mean our fight against terror is going to come to an end,” Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gul said Monday at a meeting commemorating the failed coup attempt.

Erdogan’s ruling coalition, which enjoys a majority in parliament, is expected to adopt new anti-terrorism laws that would extend many of the state of emergency measures for at least three years.

Public workers could still be arbitrarily terminated, police would be able to hold suspects accused of ties to terrorist organizations for up to 12 days without pressing charges and anyone organizing a public gathering after sunset would have to receive approval from local authorities. The government could also block people from entering certain areas for up to 15 days for security reasons.

Under a new presidential system of government in Turkey that was established early this month, Erdogan was given expanded powers to issue legislative decrees similar to the ones issued under the state of emergency. Those powers, along with the new legislation, left opposition leaders fearing the government aggressions would continue.

“With this bill, with the measures in this text, the state of emergency will not be extended for three months, but for three years,” Ozgur Ozel, who heads the parliamentary group of the People’s Republican Party, the largest opposition group, told reporters in Ankara on July 18. “They make it look like they are lifting the emergency but in fact they are continuing it.”

The state of emergency dashed Turkey’s aspirations of membership in the European Union, which has said the country would need to demonstrate a commitment to the rule of law to even be considered.

Turkey had taken “huge strides away from the European Union, in particular in the areas of rule of law and fundamental rights,” European Commissioner Johannes Hahn, said in January in announcing the findings of a regular report on the process.

The state of emergency, and the effect it has had on relations with Europe, also shook investor confidence in the Turkish economy. The Turkish lira has lost more than 70% of its value against the U.S. dollar since July 2016, including more than 25% since the start of 2018. Turkey’s leading business groups had pleaded for an end to the measures.

“We hope that the state of emergency has now been extended for the last time,” Tuncay Ozilhan, head of the advisory council for the Turkish Business and Industry Assn., the country’s largest trade association, told members in January, shortly after the emergency measures were extended by the government.

“Even if the impact of the emergency rule is limited for Turkish citizens, we quite know that its impact on foreign investors’ perceptions or investment decisions is negative.”

Farooq is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.