The good life in Xalisco can mean death in the United States

Reporting from Xalisco, Mexico — As a boy, Esteban Avila had only a skinny old horse and two pairs of pants, and he lived in a swampy neighborhood called The Toad. He felt stranded across a river from the rest of the world and wondered about life on the other side.

He saw merchants pay bands to serenade them in the village plaza and dreamed of doing the same.

He had a girlfriend but no hope of marrying her because her father was the village butcher and expected a good life for his daughter.

Then Avila found an elixir and took it with him when, at 19, he went to the United States. It was black-tar heroin, and selling it turned his nightmare into a fairy tale.

Avila was part of a migration of impoverished Mexican sugar cane farm workers that has had profound repercussions for cities and towns across America. Over the last decade and a half, immigrants from the county of Xalisco (population 44,000), in the Pacific Coast state of Nayarit, have developed a vast and highly profitable business selling black-tar heroin, a cheap, potent, semi-processed form of the drug.

Their success stems from a business model that combines discount pricing, aggressive marketing and customer convenience. Addicts phone in their orders, and drivers take the heroin to them. Crew bosses sometimes make follow-up calls to make sure addicts received good service.

The heroin networks need workers, and the downtrodden villages of Xalisco County have provided a seemingly endless supply of young men eager to earn as much money as possible and take it back home.

As black-tar heroin ruined lives in the United States, it pulled the poorest out of poverty in Xalisco. Drug earnings paid for decent houses and sometimes businesses, and it made dealers’ families the social equals of landowners. By addicting the children of others, they could support their own.

“I’d be lying if I said I was sorry,” Avila said. “I did it out of necessity. I was tired of birthdays without gifts, of my mother wondering where the food was going to come from.”

Boom times

Xalisco County begins a couple of miles south of the state capital of Tepic and spreads across 185 square miles of lush, hilly terrain. A highway curves through it to the tourist resort of Puerto Vallarta to the south.

The county seat, also named Xalisco, is a town of narrow cobblestone streets and 29,000 people. For many years, dependence on the sugar cane harvest kept the county poor. Houses had tin roofs, and few had proper plumbing.

Xalisco ostensibly still depends on sugar cane. But it is now among the top 5% of Mexican counties in terms of wealth, according to a government report.

Enormous houses with tile roofs and marble floors have gone up everywhere. In immigrant villages across Mexico, people build the first stories of houses and leave iron reinforcing bars protruding skyward until they save the money to add second stories. Often the wait is measured in years. In Xalisco, homes go up all at once.

Off Xalisco’s central plaza are swanky women’s clothing stores and law offices. Young men drive new Dodge Rams, Ford F-150s and an occasional Cadillac Escalade. Outside town are new subdivisions with names like Bonaventura and Puerta del Sol.

Xalisco’s Corn Fair, held every August, is another measure of the town’s newfound wealth. Twenty years ago, the fair’s basketball tournament was a modest affair. Teams from surrounding villages competed against one another in ragged uniforms.

Then “the boys began going north and getting into the business,” said one farmer. “The town just began to come up.”

The tournament purse grew so fat that semi-pro teams began competing. Last year, with first prize worth close to $3,000, semi-pro squads from Mazatlan, Monterrey and Puerto Vallarta competed, each with American ringers. One local village sponsored a team made up entirely of hired players, reputedly paid for by a heroin trafficker.

Sharing in this wealth to varying degrees are 20 villages scattered across the hills south of the town of Xalisco. Esteban Avila was born in one of them, a place named for the Mexican revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata.

Avila, now 35, is in a federal prison in Texas, serving a 15-year term for conspiracy to distribute heroin. He described his odyssey in interviews with The Times on the condition that he would not talk about anyone else in the drug business.

When he was a boy, the village of Emiliano Zapata was poor and notorious for its violence. In The Toad, where Avila’s family lived, roofs leaked and the hills were the bathroom. When Avila and his friends went to the village basketball court, other boys ran them off with rocks and insults.

Later, Avila wanted to join the Mexican Navy or highway patrol, but only sons of well-connected fathers were admitted, he said.

“In the United States, there’s no need to be a criminal to live well,” he said. “But in Mexico, they throw you into a dead end.”

At 14, Avila traveled to Tijuana, then slipped across the border and made his way to the San Fernando Valley.

“I wanted to look for some new way to live, something with a future,” he said. “I wasn’t going to find it in the village.”

But he didn’t want to go to school and he was too young to work. So he returned to Emiliano Zapata and bided his time working in the sugar cane fields.

In the mid-1990s, men from Xalisco began selling black-tar heroin across America. A friend who ran a heroin network recruited Avila to work as a driver in Phoenix.

Avila, then 19, accepted. Every day, he drove around the city, his mouth full of tiny, uninflated balloons, each filled with a tenth of a gram of heroin. Addicts phoned in orders. A dispatcher relayed them to Avila, who delivered the drugs to customers and collected payment.

Five months later, he took a bus back to Xalisco with $15,000 in his pocket. He was wearing new Levi’s 501s -- a prized garment in many Mexican villages.

“That night was the first time we had more than enough to eat,” Avila said.

His parents never asked how he made the money.

In the Xalisco system, drivers commonly strike out on their own after a few years and set up delivery operations. In 1997, Avila told his boss that he was going to seek his own heroin market in New Mexico.

A friend told Avila about addicts in Santa Fe, so he went there. He found those addicts and through them many more, including dozens in Taos, Xalisco’s sister city. A half hour away, he discovered the town of Chimayo, in the verdant Espanola Valley, with one of the highest rates of heroin addiction in the country. Soon, Avila’s cheap, powerful black tar drove out the powder heroin that addicts had been using.

Avila declined to reveal where he got his heroin, other than to say that Nayarit’s mountains are filled with small poppy farms and that black tar is easily made.

In Albuquerque, he bought a counterfeit birth certificate and driver’s license; he crossed the border posing as an American from then on. Back in Xalisco, he hired drivers from villages near his own, paying smugglers to bring them across the border.

“Some drivers just wanted enough to build a decent house or buy a new truck. Then they were coming back home,” he said. “Some wanted to fly, like I did.”

He returned to Emiliano Zapata and for three years managed the business from Mexico, returning to the United States only occasionally. At home, families asked him for loans; some paid him back. Poor young men asked him for work up north.

He took his family to fine restaurants in Tepic, where they nervously rubbed elbows with the city’s middle class.

“Our life changed entirely,” he said. “It gave me more self-assuredness. If you have a peso in your pocket, you feel lighter of spirit. The weight of life is easier to carry.”

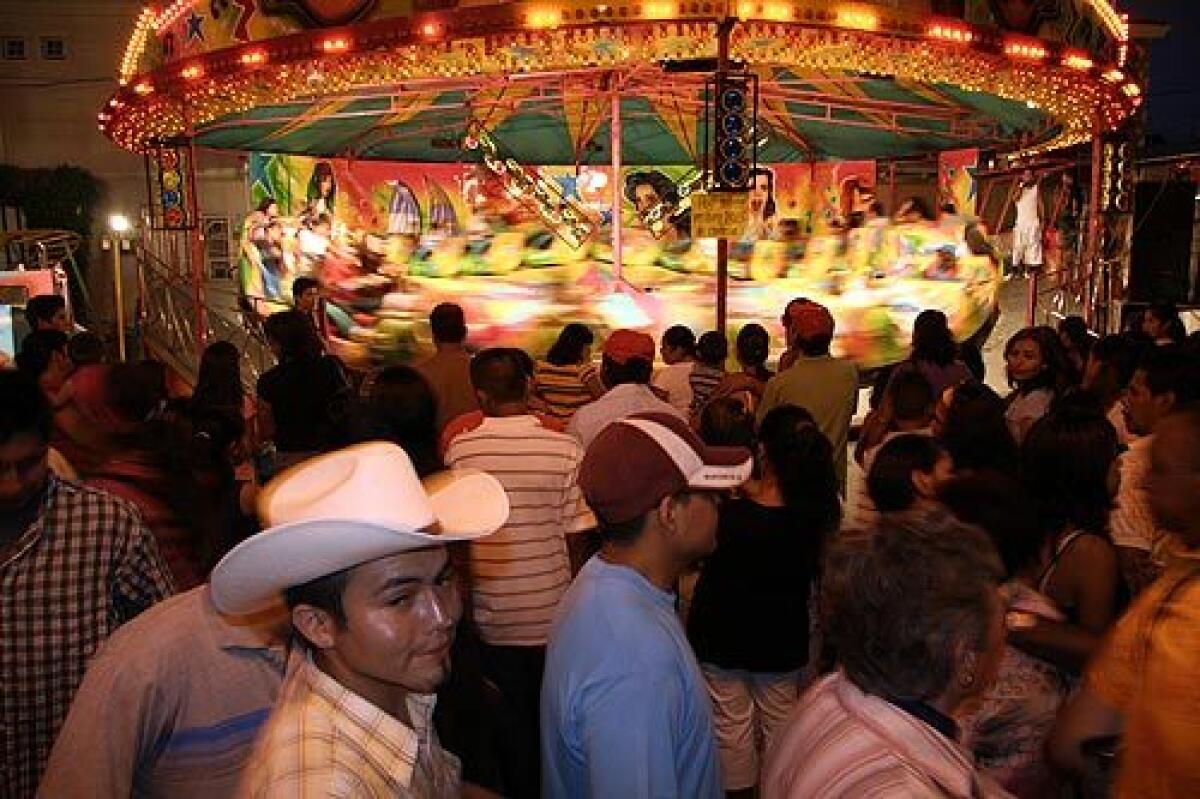

At a fiesta in Xalisco’s plaza one night, Avila and a friend paid for 11 hours of banda music, plus alcohol: a $3,000 tab.

He paid for one sister’s quinceañera and another’s wedding. He paid for a sister to attend college in Tepic, the first in her family to go.

Now he could give his girlfriend the life her parents expected. He stole her away to a Puerto Vallarta hotel for a weekend -- which in the village meant they were married.

Avila hired workers to build a house for his parents and men to help his father in the field. He hired a maid to help his mother. He moved his wife and children away from Emiliano Zapata and its violence and low expectations.

His father was greeted on village streets by those better off than he. He drank less, yelled less. One day, seeing his son with some cocaine, Avila’s father took him aside and counseled him not to use drugs and to avoid bad habits.

“For the first time, I felt he spoke to me the way a father should speak to a son,” Avila said.

Heroin opened vistas for other sugar cane cutters’ sons as well. The village’s moneyed classes no longer could talk down to farmers.

“We were all equal now,” Avila said.

Over the next decade, networks of Xalisco dealers moved across the country, often competing with one another in such cities as Columbus, Ohio; Portland, Ore.; and Nashville.

Much of the money they earned flooded south, reaching the poorest of Xalisco County, people used to cutting cane for $8 a day.

So as quickly as dealers were arrested, they were replaced by others from Xalisco betting they could elude capture long enough to return with money for a house, truck or other mark of success.

One heroin driver from the village of Aquiles Serdan built a house with an electric garage-door opener, awing his neighbors.

Another former sugar cane worker, speaking on condition of anonymity, described the impression made by the device. “Everybody watched while the door went up by itself,” he said. “People would walk by and look at it.”

Seeing young men his age return from the United States with money, this man decided he wanted some too. He became a heroin driver in a southeastern U.S. city.

“I had a wife and son and I couldn’t support them,” he said. “I thought I’d buy land, and build us a house.” He said half the young men in Aquiles Serdan left to try their luck as drivers.

In his first six weeks last year, he earned $7,000, more than he’d ever had at one time. Then he was arrested. He pleaded guilty to distributing heroin and faces up to 10 years in prison.

Back in Aquiles Serdan, 20 new houses have gone up, several with electric garage doors.

Operation Tar Pit

In 2000, Esteban Avila’s fairy tale ended. He was among nearly 200 people arrested in a dozen cities in a federal investigation dubbed Operation Tar Pit. The case began in Chimayo after a rash of overdoses -- 85 deaths in three years, representing 2% of the town’s population.

The arrests marked the first time the Drug Enforcement Administration had pieced together the national reach of Xalisco dealers. In Xalisco, the busts had an almost recessionary effect. “The fiesta was dead. Nobody was coming to the plaza,” said a man who lived there at the time, speaking on the condition that he not be identified.

The easy money Avila made turned out to be the hardest of his life. His children are growing up without him.

Still, heroin lifted his family’s horizons. Avila believes that poor people get no breaks they don’t make for themselves. Had he been able to achieve anything by legal means, he would have, he says.

The truth of that is hard to know. But it does seem that black-tar heroin, as it destroyed lives in America, remade his own in Mexico and channeled his gumption unlike anything else available to him at the time.

“At least I’m not going to die wanting to know what’s on the other side of that river,” he said from prison. “I already know.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.