Palestinian in Kafkaesque battle over family’s hotel

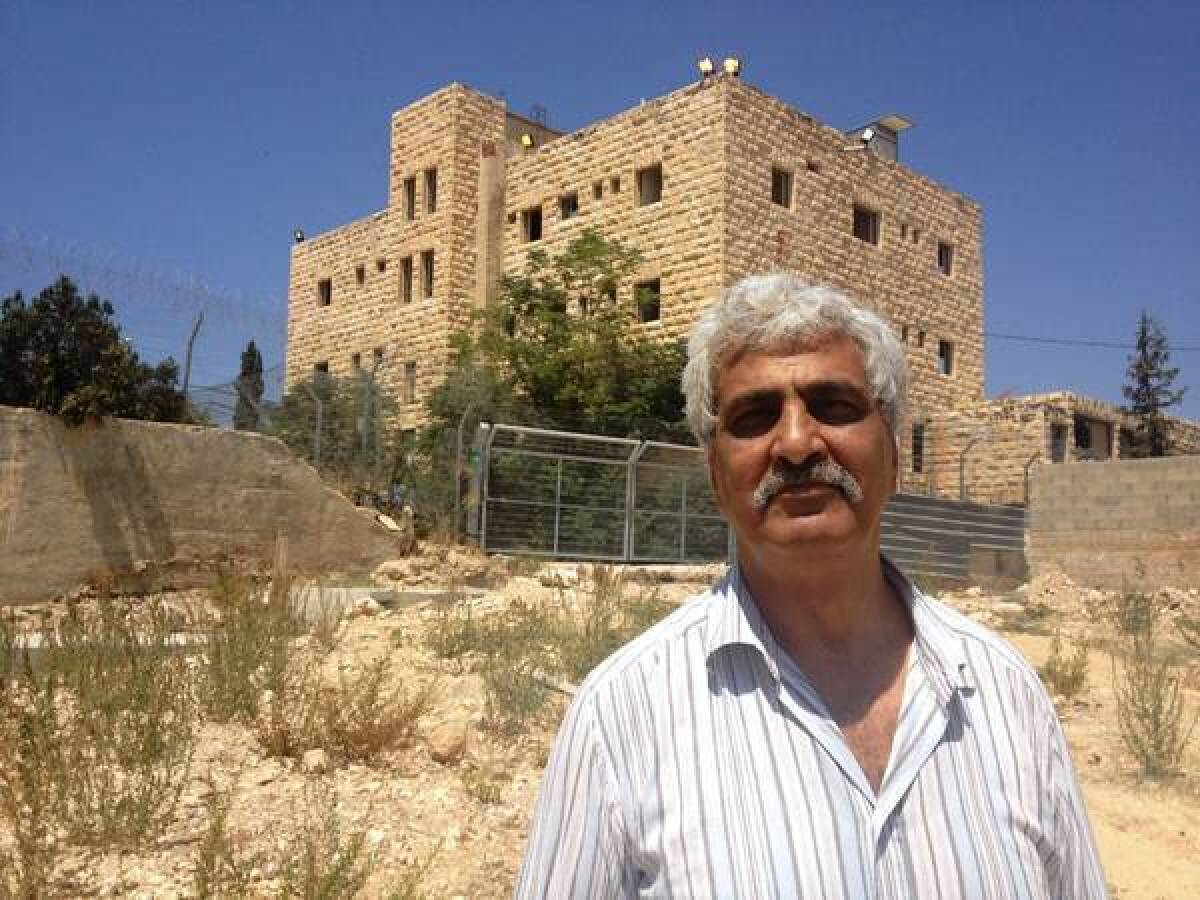

ABU DIS, West Bank — The year Ali Ayad was born, his father broke ground on a majestic home perched on a bluff overlooking Jerusalem, with views of the Dead Sea in one direction and the golden Dome of the Rock in the other.

For all of his 59 years, Ayad’s life has revolved around the 1-acre plot. He played under the olive trees as a boy and became manager after the home was converted into the Cliff Hotel.

He met his Norwegian wife from behind the reception desk, married her in the dining room and raised two daughters amid the daily bustle of visiting tourists and diplomats.

But the idyllic life turned into what he describes as a Kafkaesque nightmare a decade ago after Israel seized control of the hotel. Using a combination of military orders and a controversial absentee-owner law, the government kicked him off the property, banned him from returning and then confiscated it as abandoned.

Israel informed Ayad, who has always been identified by Israel as a West Bank resident, that his former home was inside the Jerusalem city limits, even though for decades the municipality refused to provide public services because it said the property was in the West Bank town of Abu Dis.

Last month, as the family was preparing for a long-awaited hearing before the Supreme Court, Israel abruptly dropped the absentee-ownership claim. But victory parties were short-lived when it became apparent that the government had simply moved the goal post.

The state is still moving to confiscate the hotel, which rests in the path of Israel’s security barrier and near a Jewish settlement, for unspecified “security” reasons.

“They’ve tried every trick in the book,” said Ayad, who hasn’t been permitted to set foot on the property since 2004 though he lives just a few blocks away. “I’m living in a Greek tragedy. I’m exhausted from this. I’m totally drained. Obviously they just want me to give up. But I have no right to give up.”

The most galling part, he said, was the claim that he was an absentee owner.

“I had to spend 10 years proving that I was not absent and that I exist,” he said. “You sit there in court listening to them discuss you as if you are not there. You want to yell, ‘I’m not absent! I’m right here!’”

On Tuesday, he plans to attend the Supreme Court hearing, though that aspect of the case may be moot in light of the government’s reversal, which he suspects was “another legal maneuver.... We weren’t even sure whether we should celebrate, so a friend brought over only a very cheap bottle of champagne. It gave me a terrible hangover. Just like my case.”

Representatives from the Israeli military, which controls the West Bank, and the city of Jerusalem declined to comment. Each party insisted that the Cliff Hotel was not part of their authority and directed media inquiries to the other.

Justice Ministry officials also declined to comment, citing the lawsuit. In a statement last month, the ministry recommended returning the property to the family in keeping with the now-dropped absentee claim. But the statement noted that the property is still subject to the government’s outstanding security claims.

The shift in Israel’s legal strategy became evident early this year, when the finance minister notified the family that the hotel was being confiscated for security reasons.

The notice puzzled the family because the hotel had been confiscated in 2003 under the 1950 Absentee Property law, which was originally used to seize property owned by Palestinian refugees who fled their homes during the 1948 war after Israel’s creation.

“How can the government confiscate something that it has already confiscated?” Ayad asked.

Equally confusing, he said, was the claim that the hotel is inside Jerusalem, making it subject to Israel’s absentee law.

For decades the city of Jerusalem refused to provide sewage service and did not collect municipal real estate taxes. Ayad said all Israeli-issued licenses and permits for the hotel since 1967 — when Israel seized control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem — were handled by the Bethlehem office of the army’s Civil Administration, which supervises civilian aspects of the occupation. The hotel was listed in Israeli government brochures as a West Bank attraction.

Ayad is convinced that Israel quietly changed the border to include the hotel.

But Palestinian mapping and border expert Khalil Tafakji said the Cliff Hotel has been considered to be a few yards inside Jerusalem since Israel annexed East Jerusalem and redrew the city’s borders after 1967. He noted that the annexation has never been internationally recognized.

Tafakji said Israel probably never looked closely at the boundary until the 1990s, when the Oslo peace accords began a process of dividing the land between Israelis and Palestinians. Scrutiny was further intensified when Israel began constructing the security barrier and wanted to expand a nearby Jewish settlement.

“This issue isn’t about security,” he said. “It’s about the demographics of Jerusalem.”

Over the years, Ayad said, the government has tried various methods to gain control, such as offering to buy the land and once suggesting the property had been purchased by Jews in the 1930s, though that claim was retracted. On several occasions before it was confiscated, soldiers raided the property in the early morning hours and evacuated occupants in order to conduct live-ammunition exercises outside.

Today the once-thriving Cliff Hotel looms atop the hill like a ghost house, falling apart and mostly deserted save for the Israeli soldiers who patrol past barbed wire fencing. The lemon trees and grapevines are long dead. Nearly every window is broken.

The barrier — which Israel began installing a decade ago to separate itself from the West Bank — runs up to the edge of both sides of the property. But because of the ongoing litigation, the dilapidated hotel remains one of the only remaining gaps in the wall that divides Jerusalem from the West Bank.

Walking as close to the property as he dared without provoking soldiers, Ayad pointed to the garden where guests once passed summer evenings, to the bar and billiards room, to the campgrounds once popular with German tourists.

“It was a good life,” said Ayad, adding he doesn’t like dwelling on the past. “I don’t like to think about those memories. I don’t want it to seem like a lost dream. That might mean it’s something I will never get back. So no more emotion. If I treated this in an emotional way, I would have been dead years ago.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.