For Peruvian presidential candidate, the Fujimori name is an asset and a curse

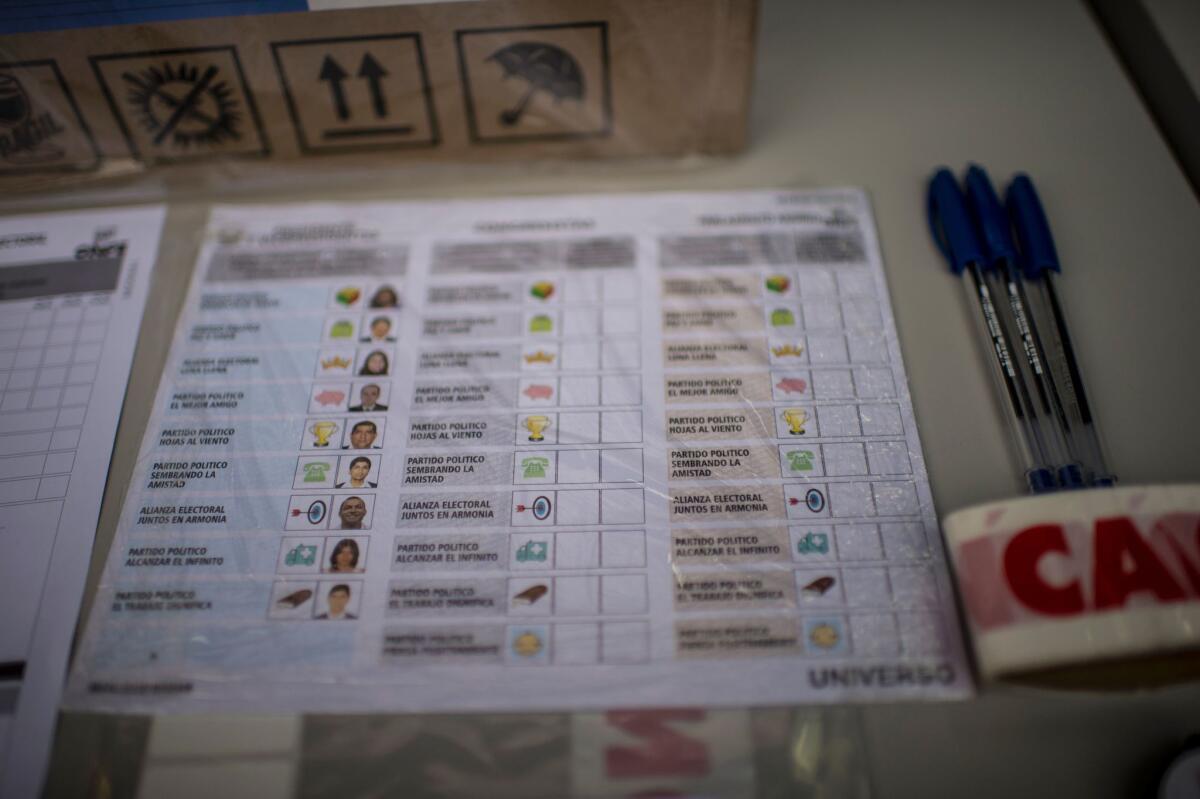

A Peruvian ballot at a polling station in Lima on the eve of presidential and general elections.

Reporting from Lima, Peru — Keiko Fujimori’s biggest obstacle to outright victory in Peru’s presidential election Sunday is not any of her nine opponents but the stigma of her surname.

Her father, Alberto, the disgraced former president, is now serving a 25-year prison sentence for human rights crimes.

Keiko Fujimori is expected to take the most votes Sunday — up to 40%, according to polls. If no candidate wins half the vote, the top two finishers will face each other in a June runoff.

That’s a vote the 40-year-old Fujimori would rather avoid. Many observers believe that her support may have already hit a ceiling and that she would lose Round 2 despite winning Round 1. That’s what happened to her in the 2011 presidential election.

“She’s been elected to Congress with the highest number of votes of any other candidate and I believe she is ready to be Peru’s first female president,” said David Scott Palmer, a Latin American political science professor at Boston University. “But her problem is her last name.”

Her father was president from 1990 to 2000 and among much of the population is remembered for suspending Congress and the constitution to expand his own powers and turning a blind eye to bribery and arms and drug trafficking by his spymaster, Vladimiro Montesinos.

In 2009, a Peruvian court found the ex-president guilty of corruption and human rights abuses, including authorizing extrajudicial killings by death squads. He is also suspected of having authorized the sterilization of as many as 300,000 indigenous women.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Antipathy toward him runs so deep that one recent poll found that 45% of Peruvians wouldn’t vote for his daughter under any circumstance.

Last Tuesday, the 24th anniversary of the former president’s suspension of Congress, 50,000 protesters took to the streets of Lima in a march against both Fujimoris.

One protester, Alicia Peñaque, a 32-year-old sociologist, said the demonstration was a reminder of “systematic violation of human rights, destruction of state institutions and the use of state resources for repression and assassination.”

Another, Alonso Ruiz Timoco, a 22-year-old university student, said electing Keiko Fujimori would mean a return to repression.

Despite such sentiments, it seem unlikely that she would have ever gotten this far in politics without her lineage.

A significant number of Peruvians still revere her father for defeating the Shining Path guerrilla group, stamping out hyperinflation and putting the economy on track for a decade of growth.

Keiko, the eldest of his three children, was 15 when he became president. He made her first lady in 1994 after separating from his wife.

She went on to earn a master’s in business administration from Columbia University and in 2006 was elected to Congress, where she served two terms and earned high marks as a hard worker, public speaker and moderating influence in her center-right party, Fuerza Popular.

“Keiko is clear, straightforward and smart,” said John Youle, president of the Lima-based risk analysis firm Consultandes. “She has spent the last five years working hard in remote areas to build an organization and to reach the people.”

Not surprisingly, she has been trying to distance herself from her father.

During a television debate this week, she signed a list of promises to never repeat his autocratic policies.

“Looking straight into the eyes of Peru, I make this commitment,” she said. “Looking at my country’s history, I know which chapters to repeat and which ones not to.”

She also promised to not seek a pardon for her father and to make reparations to the sterilized women.

While the polls strongly favor Fujimori on Sunday, they are less certain about who will finish second to face her in a possible runoff.

Among the strongest contenders is Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, a 77-year-old former finance minister who is also a centrist. One poll shows him beating Fujimori in a runoff.

Also gaining strength in recent polls is 35-year-old Veronika Mendoza, a socialist member of Congress who is promising to reform large-scale mining operations that have become increasingly unpopular for causing pollution and driving up local prices.

Special correspondent Leon reported from Lima and special correspondent Kraul reported from Bogota, Colombia.

ALSO

Mexican state of Baja California balks, again, at banning bullfighting

When Brazilian politicians talk about a coup, they trigger fears of a return to a dark past

After massive ‘Panama Papers’ document leak, rich and powerful around the world deny wrongdoing

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.