Slaying of James Foley revives debate on paying ransom to terrorists

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — On Nov. 26, 2013, a year after James Foley was kidnapped in Syria, his parents and his employer received an email in English from his captors. They offered to prove that the American journalist was alive by giving his family the chance to ask three personal questions.

The answers came back, all correct.

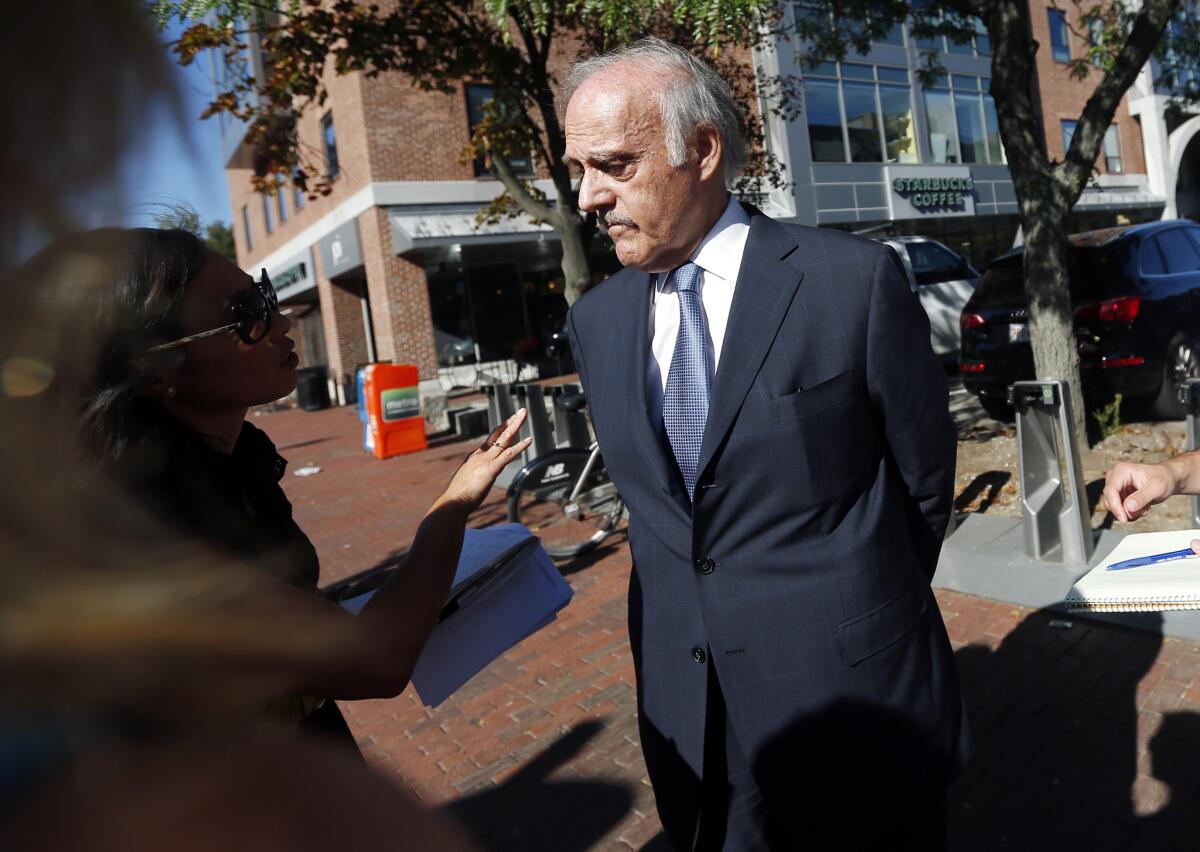

“That was such an incredible moment,” Philip Balboni, president of GlobalPost, the online news organization that had hired Foley, said Thursday. “This gave us hope that we could negotiate his release.”

But the next email came with a ransom demand: $132 million, or release of several prisoners held by U.S. authorities.

The Foleys and GlobalPost began to quietly raise the money, even though the U.S. government has clear policies against giving money to a terrorist organization such as Islamic State, the heavily armed Al Qaeda spinoff that was holding Foley. FBI and other officials, who were given a copy of the emails, did not try to stop them.

“The appropriate arm of government was aware of every action that we took,” Balboni said. “We were never told to stop doing what we were doing.”

But then the captors stopped communicating. The Foleys did not hear from them again until Aug. 12, when they received another email. This one was a message to the American government “and their sheep-like citizens,” one filled with rage about U.S. airstrikes against Islamic State positions in northern Iraq and threatening to execute the journalist in retaliation.

Although it’s impossible to know whether the militants would have freed their captive for cash, the grisly video of Foley being decapitated by a masked militant has rekindled an emotional debate over whether U.S. policy that bars negotiating with terrorists or paying ransoms helps or hurts Americans.

Like other terrorist groups, Islamic State has used kidnappings to raise money. In April, the group released four French and two Spanish journalists, reportedly for large ransoms. The last email to the Foleys complains that the U.S. has not arranged “the release of your people via cash transactions as other governments have accepted.”

Obama administration officials said Thursday that they see no reason to revisit the policy. Paying money gives terrorists an incentive to seize more Americans, and bankrolls future terrorist acts, they argue.

“Our policy is clear,” said Caitlin Hayden, spokeswoman for the National Security Council. “The United States government, as a matter of long-standing policy, does not grant concessions to hostage takers. Doing so would only put more Americans at risk of being taken captive.”

But the policy is not always so clear. In the Iran-Contra scandal of the mid-1980s, the Reagan administration sold missiles to Iran, the subject of an arms embargo, in a failed attempt to win the release of American hostages held in Lebanon.

And in May, the Obama administration released five Taliban detainees from the U.S. prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in exchange for Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, who was captured in Afghanistan and held by the Taliban for five years.

U.S. officials said they made the deal through government intermediaries in Qatar and so did not directly negotiate with terrorists.

On Thursday, the Government Accountability Office, an audit agency, said in a legal opinion that the Department of Defense violated the law because it failed to notify relevant congressional committees 30 days before the prisoners were transferred, and used money not intended for moving detainees from Guantanamo Bay.

Pentagon spokesman Rear Adm. John Kirby responded that the trade was lawful and was made after consultation with the Justice Department.

“The administration had a fleeting opportunity to protect the life of a U.S. service member held captive and in danger for almost five years,” he said. “Under these exceptional circumstances, the administration determined that it was necessary and appropriate to forgo 30 days’ notice of the transfer.”

Adam Ereli, a retired U.S diplomat who served in the Middle East, said the White House was willing to bargain for hostages in both cases.

“The question is, what are the terms of trade? Some terms of trade are off the table, but others are acceptable,” said Ereli, vice chairman of Mercury, a Washington public relations firm.

The question is whether extremist groups such as Islamic State offer a meaningful basis for negotiations.

“You end up with a brutal actuarial problem where more and more money is sent to fund forces you’re trying to defeat,” said Anthony Cordesman, a former intelligence director at the Pentagon now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

At least officially, most major countries vow not to pay for hostages. In 2013, under prodding from the U.S. and British governments, the Group of 8 leading industrialized nations announced that they “unequivocally reject the payment of ransom to terrorists.”

But unofficially, many do. France, Germany, Italy and Spain are among the nations that directly or indirectly pay ransoms, say former U.S. officials. The governments deny doing so, but they often use complex intermediaries to provide deniability, the officials say.

In a 2012 speech, David Cohen, the U.S. Treasury official in charge of disrupting terrorist groups’ finances, said nations had paid more than $120 million in ransoms for their citizens since 2008. The money has gone to Somali pirates, Al Qaeda franchises, Mexican drug cartels and other groups.

Daniel Benjamin, the State Department’s counter-terrorism coordinator from 2009 to 2012, said the Obama administration has tried to persuade other governments to stop paying ransoms, but has met strong opposition because officials face strong public demands to have their citizens freed.

“It’s been nothing short of disastrous that so many countries have lined the pockets of so many terrorist organizations,” he said.

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, based in North Africa, “is a mediocre terror organization, but it’s got an extremely efficient kidnapping organization, and it’s been kept in the field by European nations,” said Benjamin, who is now with Dartmouth University.

In 2010, France arranged for $17 million to be paid to the group to free French hostages seized in Niger, according to U.S. officials.

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, one of the terrorist network’s most dangerous franchises, extorted $20 million in 2012 and 2013 in ransom money, according to Alistair Burt, a former top British diplomat for the Middle East.

Ransoms helped fund the militants’ campaign to seize and hold towns in southern Yemen in 2011, U.S. and European officials have said. The money paid the salaries of the fighters and compensation to families of the dead, as well as funding social services and infrastructure in occupied towns, the officials said.

U.S. officials discourage families or private companies from paying ransom, but the government doesn’t block them. Many corporations are insured against ransom demands and pay them without public notice, former officials said.

Matthew Levitt, the former top official at the Treasury Department on terrorism financing, said it was unclear whether Islamic State had been serious about the ransom for Foley, because the sum was so high.

“This has generated them a huge amount of publicity,” said Levitt, now with the nonpartisan Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “Just because they asked for money, that doesn’t mean it’s what this was all about.”

Foley’s family obviously hoped to win his release. After getting the Aug. 26 email, the family wrote back, pleading for his life, saying he had nothing to do with government policy and had deep respect for Islam.

The Foleys got no response. So they waited, hoping the final email was a bluff.

Hennigan and Richter reported from Washington and Semuels from New York. Times staff writers Christi Parsons in Edgartown, Mass., and Kathleen Hennessey in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.