Vanessa Gutierrez began to notice the sores and rashes on her 5-month-old in May 2019. Around the same time, her other daughter, 9, experienced asthma flare-ups.

The administrative assistant from Sacramento was baffled about what could be harming her children.

For the record:

2:53 p.m. Aug. 31, 2022An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the class-action lawsuit against Zinus that included a claim by Vanessa Gutierrez was filed in March 2020. The only plaintiffs in the complaint at that time were Amanda Chandler and Robert Durham. The suit was amended to be a class action in April 2021.

“The baby got the worst of it,” Gutierrez said. “I thought she was overactive, but it was because she was feeling the burning.… It looked like little paper cuts all over the back of her legs.”

Newsletter

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

After hours of internet research, Gutierrez grew convinced the culprit is what many of us spend up to one-third of our lives on: a mattress. She is now the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit filed in Sacramento in July against the manufacturer of her mattress, Zinus Inc., alleging flame-resistant fiberglass fibers in the South Korean company’s products can escape and cause health problems, including skin and respiratory tract irritation, and persistent environmental contamination.

The lawsuit is one of a handful filed against manufacturers of so-called bed-in-a-box mattresses containing fiberglass. The complaints come at a moment when e-commerce has created new opportunities and competitive pressures for mattress makers, minting billion-dollar brands seemingly overnight. Meanwhile, new regulations and shifting consumer preferences have driven changes to the materials used in bedding, but labeling requirements have lagged, leaving some shoppers surprised when the mattress they thought was chemical-free turns out to contain a material better known for its use in home insulation and fishing boats.

Fiberglass — a composite of plastic and glass — is supposed to make mattresses safer. Although they can cause irritation of the eyes, nose and throat, man-made vitreous fibers “are not known to be associated with long-term health risks,” according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

U.S. and California regulations have long required furniture makers to meet standards for flame resistance. For decades, they relied on chemicals such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers, tris phosphate (TCEP) and chlorinated tris (TDCPP) to accomplish that. But research in the late-1990s and 2000s showed them to be toxic to humans, causing cancers, endocrine system disruption and other health problems. TDCPP and TCEP are identified as carcinogenic under California Proposition 65.

The profusion of warnings stemming from California’s landmark consumer safety law has left shoppers overwarned, underinformed and potentially unprotected, a Times investigation has found.

The state banned the use of potentially toxic flame-retardant chemicals in upholstered furniture beginning in 2015, with compliance optional for mattress makers. In 2018, the state extended the ban to mattresses and added additional chemicals to the list, with the new restrictions going into effect in January 2020.

A number of low-cost mattress makers responded by turning to fiberglass as a substitute, said Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit advocacy and research group focused on toxic chemicals and corporate accountability. According to the Gutierrez lawsuit, using another fire-resistant material instead of fiberglass adds about $5 to the production cost of a mattress. Stoiber called it “a regrettable substitution. Fiberglass shouldn’t be used in mattresses if it’s clear that people are being harmed by it.”

Citing “numerous public complaints” of fiberglass exposure from mattresses, officials from California’s Department of Public Health published a study on the topic in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in February.

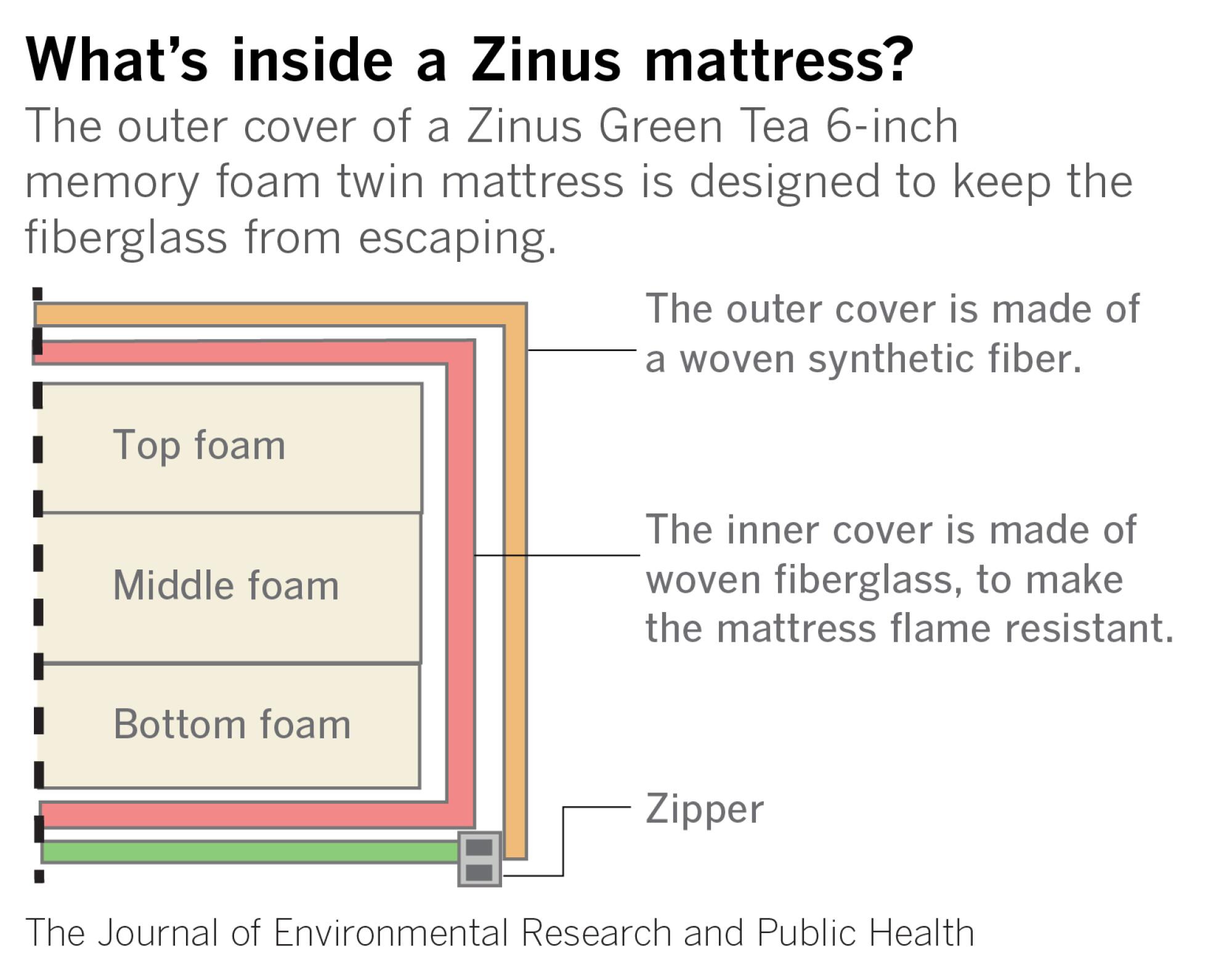

In a test of four e-commerce mattresses, the researchers discovered fiberglass in two — one of them a memory foam mattress made by Zinus, the other an infant mattress made by Graco. An examination of those mattresses found that up to 1% of the fiberglass strands migrated from the inner sock layer to adjacent layers, “representing a potential risk of consumer exposure if the zipper on the outer cover is opened.” The authors noted that the fibers used “are potentially inhalable into the nose, mouth, and throat, but are likely too large to penetrate deeper into the lungs.” Children and infants are more susceptible to skin and lung irritation from fiberglass, they wrote.

The authors also noted that ambiguities in federal and state labeling requirements led to discrepancies in whether and how mattress makers disclosed the presence of fiberglass, with makers able to advertise mattresses as “chemical-free” on the basis that fiberglass is present in an outer layer rather than the foam pad itself.

“There’s no law that says that a company has to tell you every single thing that’s in a mattress,” said Bobbi Wilding, executive director of Clean and Healthy New York, an environmental health advocacy organization. “So whatever they tell you is what they’re choosing to tell you, and that leaves people incredibly vulnerable because you have to just rely on what they say.”

Based in South Korea, Zinus has a U.S. subsidiary in Tracy, Calif., and a distribution warehouse in San Leandro, Calif. The case in which Gutierrez is a plaintiff was filed as a class-action suit on behalf of all U.S. buyers and users of Zinus mattresses, but a judge must first approve the class status before it can proceed. The suit does not specify a dollar amount in damages but requests that the court declare the mattresses in question defective and order Zinus to stop selling them and reimburse the plaintiffs for all cleanup and damages costs.

In a statement, Zinus said the fire-resistant material in its mattresses is standard in the industry and is not considered hazardous by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The company also said the mattress labels warn buyers that the cover should not be opened or removed. (Graco did not respond to requests for comment.)

Mattresses can be costly, with prices ranging from a few hundred dollars to well into the thousands. Zinus mattresses are priced on the affordable end, ranging from $100 for a twin mattress to about $900 for a king size.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The model Gutierrez purchased for her bed was certified by the nonprofit CertiPUR-US, an organization that tests bedding for emissions, content, performance and durability. But the certification guarantees only that the foam inside the mattress is free of any toxic flame retardants such as PBDEs, TDCCP or TCEP. It does not reflect the content of the fiberglass-containing inner cover layer.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission said fiberglass use in mattresses should not be a hazard to consumers as long as the protective outer cover is not removed or opened. “Most consumer complaints about fiberglass being released from mattresses that have been reviewed by staff involved the outer cover being removed or damaged,” the commission said in an emailed statement. “If the outer cover remains intact, then the exposure to fiberglass particles is expected to be minimal.”

Some Zinus plaintiffs said they removed the protective outer cover, not knowing it was supposed to be left on. The lawsuit alleges that the “DO NOT REMOVE COVER” labels on Zinus mattresses were inadequate because they failed to notify users about the risk of fiberglass exposure, and because the existence of a zipper on the cover suggests it can be opened.

Gutierrez said she had never removed or opened the cover at the time she noticed her children’s symptoms. The lawsuit quotes a number of Amazon.com reviews by verified buyers who say they also encountered fiberglass despite never opening or damaging the outer cover.

According to the suit, the mysterious health problems continued for nearly 2½ months and several unsuccessful doctor visits until Gutierrez noticed shards of crystalized fibers on her black work pants and took to the internet to figure out the source.

Subsequently, Gutierrez said, she discovered fiberglass particles throughout her 1,100-square-foot apartment. The particles, she said, infiltrated her heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, spreading from her room, where the baby also slept, to the living room and her older daughter’s room.

Unable to remove the fibers from her clothing or furniture, she put most of her belongings in a storage unit, where they remain, along with the mattress. All told, a product Gutierrez purchased from Amazon for $400 ended up costing her nearly $20,000 in unsalvageable household items, remediation costs and medical bills, according to the lawsuit.

“I remember crying like I was at a funeral because I couldn’t believe this was happening,” she said. “A lot of these clothes I’ve had for many years…. But it was all gone.”

In a message reviewed by The Times, Zinus offered Gutierrez $1,000 in compensation, an offer she rejected.

According to a demand letter sent by her attorney in March, Shasta Uhler, a San Diego resident, had similar problems with a Signature Sleep mattress containing fiberglass, which she purchased from a third-party seller on Amazon.com in late 2020. She said that she was exposed to the fibers for 72 hours after unzipping and removing the protective cover, and that they caused her to suffer from inflamed lungs.

In an email statement, Dorel Home Furnishing, the parent company of Signature Sleep, said it could not reach Uhler to discuss her problems with her mattress.

“Protecting our customers from fire hazards is both federally required and an important safety priority,” the company said.

The class action against Zinus has its roots in a lawsuit filed by Cueto Law in Belleville, Ill., on behalf of Amanda Chandler and Robert Durham of Collinsville, Ill. They say fibers were released from their mattresses when they unzipped the outer protective covers.

According to the suit, fiberglass contamination spread throughout the couple’s home, causing them to be displaced to a hotel for months. The couple suffered tens of thousands of dollars in property damage and spent more than $20,000 for professional remediation services, according to the suit.

In April 2021, the suit was amended to include Gutierrez and hundreds of other plaintiffs. . A district judge dismissed the claims from non-Illinois residents including Gutierrez in June, finding no connection between their claims and Zinus’ dealings in Illinois. The cases were dismissed without prejudice, allowing the firm to file a new lawsuit representing Gutierrez in California.

“It’s not hyperbole to say that this has ravaged thousands of individuals’ lives from across the United States,” said James Radcliffe, a personal injury lawyer with Cueto Law.

Gutierrez said her family still feels the effects of the fiberglass exposure three years later. Her daughter, now 4 years old, still has visible scarring on her chest and calves, she said.

“All that time and safety was lost,” Gutierrez said. “I didn’t feel like we had a safe place for a long time after. I thought I was providing a good home for my daughters, but I purchased the poison we were sleeping on.”

More to Read

Updates

2:53 p.m. Aug. 31, 2022: Following publication of this article, a Zinus spokesperson supplied an additional statement:

A lawsuit and related misinformation campaign is misleading consumers about the type of mattress materials used to comply with fire regulations and protect our customers. The type of chemical-free fire safety material that we use is standard in the mattress industry across all price points. The Consumer Product Safety Commission has found that this type of material is “not considered hazardous,” and various regulatory agencies and authoritative scientific bodies have concluded that exposure to this type of material does not pose a risk of chronic health effects. To protect the internal fire barrier, customers should not remove the outer mattress cover. The label discloses the contents of the mattress and warns against removing the outer cover. Zinus mattresses currently being sold include locked zippers without pull tabs and an additional sewn-in label that warns against removing the outer cover. For all these reasons, we look forward to defending the composition and construction of our products in court, should that be necessary, and are confident we will prevail.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.